Lewis Theobald

by William Hogarth

1736 (pub. 1794)

Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University Library, Hogarth 794.01.20.05 Impression 2 Box 135

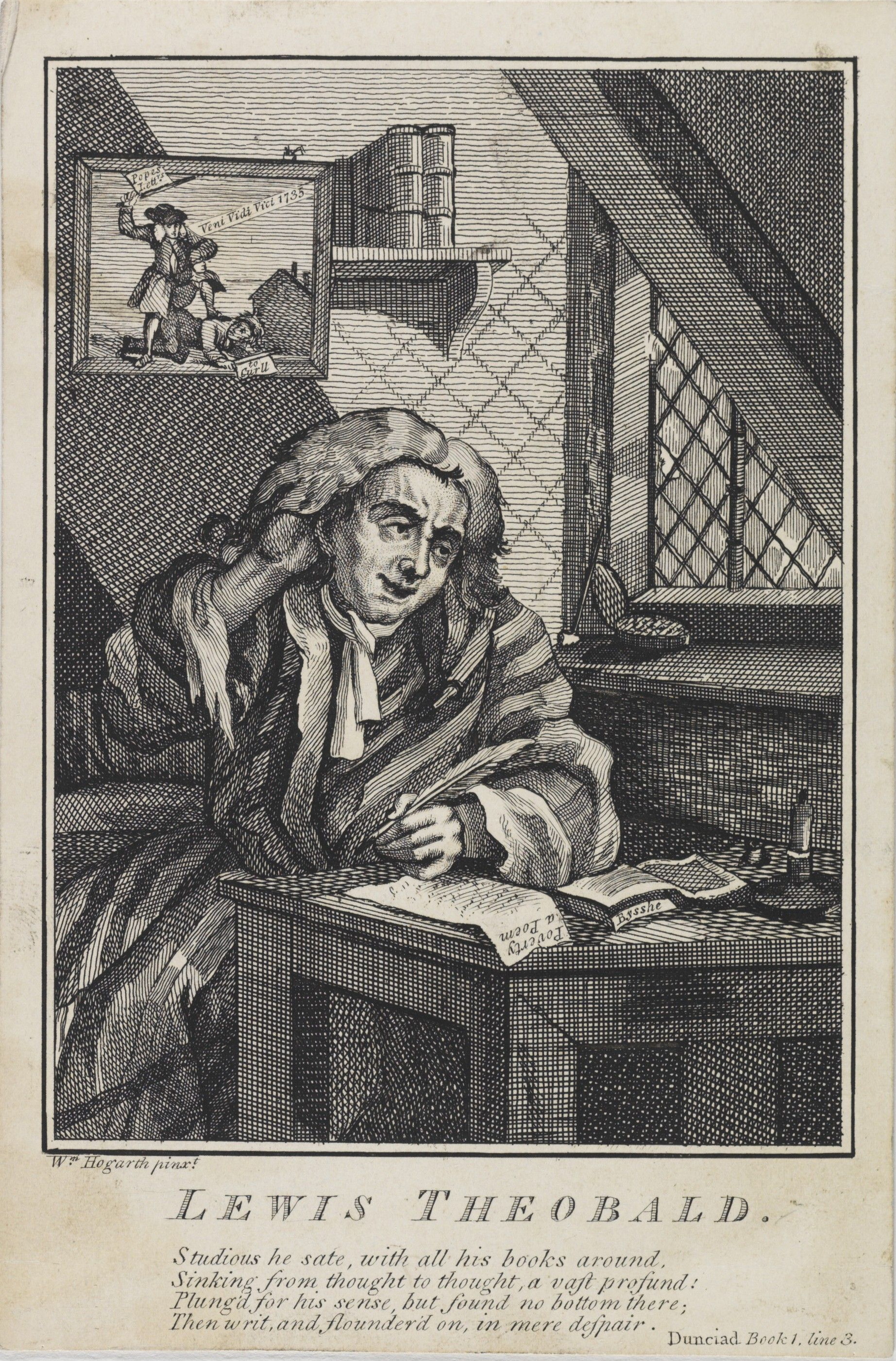

Copy of a detail from Hogarth's "Distressed poet." This version of the image, published in 1794 after Hogarth's death by Wm. Richardson of Castle St. in Leicester Fields, identifies the poet as scholar Lewis Theobald. Theobald was one of the “scriblers” employed by the unscrupulous bookseller Edmund Curll, as Alexander Pope’s favoured son of the Goddess Dulness “Tibbald.”

Pope had had a feud with Theobald since Pope’s Works of Shakespear (1725) had prompted Theobald’s rebuke in Shakespeare Restored; or, A Specimen of the Many Errors As Well Committed As Unamended by Mr. Pope, in His Late Edition of This Poet (1726). Theobald had further antagonized Pope when, working as attorney for the heirs of Pope’s mentor and friend William Wycherley, he had secured the rights to Wycherley’s poems. The Posthumous Works of William Wycherley Esq; In Prose and Verse. Faithfully Publish’d from His Original Manuscripts, by Mr. Theobald was published in 1728 by sometime business partners of Curll, A. Bettesworth, J. Osborn, W. Mears, W. and J. Innys, J. Peele, T. Woodward, and F. Clay. Pope had worked closely with Wycherley between 1705 and 1710 editing and revising the poems with an eye to eventual publication, though Wycherley had ultimately decided against printing the verses. Much to Pope’s indignation Theobald’s edition tainted Wycherley’s reputation with its inclusion of unfinished pieces and verses falsely attributed to Wycherley. Moreover, Theobald had made editorial changes to the poems and made no acknowledgment of Pope’s work. Pope’s Dunciad (1728) and Dunciad Variorum (1729), in retaliation, crowned Tibbald the King of Dunces.

The print quotes from Pope's description of Tibbald attempting to write great verse:

Studious he sate, with all his books around,

Sinking, from thought to thought, a vast profund:

Plung’d for his sense, but found no bottom there;

Then writ, and flounder’d on, in mere despair.

Dunciad Book 1, line 3

Knocking his wig askew as he scratches his head, Tibbald scribbles out “Poverty a Poem”—Theobald’s “The Cave of Poverty, a Poem. Written in imitation of Shakespeare“ (1714). A copy of Edward Bysshe’s The Art of English Poetry (1702), a handbook for poets, lies open on the table. Bysshe's manual, with its “Rules For making English verse,” rhyming dictionary, and all the “Most Natural, Agreeable, & Noble Thoughts” of the English poets listed alphabetically by subject, suggests a dull, pedantic, and unoriginal approach to poetic expression.

The painting behind Tibbald appears to be a commentary on the avaricious trade in authors’ works by greedy booksellers and complicit writers and editors unequal to the task of original composition. The image features Pope and the bookseller Edmund Curll, another of Pope’s dunces. Though commenters have suggested that Pope is thrashing Curll here, the opposite seems more likely. Lying on the ground, physically weaker with a curved spine and in the signature pose and cap from Vertue's 1722 portrait that appears in many later portraits and caricatures, this figure seems a truer depiction of Pope who would have hardly resembled the able-bodied man looming over him.

Assuming this is the case, Curll uses what seems to be a printer's pole with a page draped over it bearing the title “Popes Letters” (Mr. Pope’s Literary Correspondence for Thirty Years; from 1704 to 1734, which Curll had pirated to capitalise on Pope’s popularity and likely also to embarrass him by exposing his private—occasionally bawdy and vain—discourse with friends). Pope holds a rolled page bearing the text “to Curll,” a reference to his duping Curll into publishing the letters so he in turn could publish his own authorised Letters of Mr. Alexander Pope, and Several of His Friends (1737). The speech balloon issuing from Curll, reading “Veni Vidi Vici 1735,” quotes Curll’s introduction to the second volume of his pirated Correspondence (1735), in which he proclaims as the fictitious Philalethes: “in regard to all the Attacks which have been made upon him [Curll], by this petulant little Gentleman [Pope], especially the last, ‘VENI VIDI VICI.’”

Tibbald here represents the hack’s complicity in the production of unauthorized publications in an exploitative industry where the original creators had virtually no rights in their works. Copyright was owned by the publishers of a work, and, in the spring of 1735, London booksellers were campaigning for a bill that would extend the term from fourteen years. Pope’s concern about the bill was that there should be protection for authors, and this provided another, more immediate objective for his trick on Curll, that is, to have the pirated edition appear before the bill passed. Pope and Hogarth shared a purpose in the spring of 1735: Hogarth’s works were also flagrantly pirated—particularly egregiously, The Harlot’s Progress by Elisha Kirkhall in 1732. Hogarth himself had been campaigning for a bill to ensure engravers the exclusive rights to their own works, which received Royal Assent on 15 May 1735.

A larger view of the room shown here is found in Hogarth’s painting “The Distressed Poet” of 1736, which has hanging behind the poet a print of Pope as an ape, from the frontispiece to Pope Alexander’s Supremacy and Infallibility Examin’d (1729). The print of “The Distrest Poet” first published on 3 March 1736 shows Pope and Curll, as in the print shown here; a third variation published on 15 December 1740 shows a map titled “A Plan of the Gold Mines of Peru,” and the poem titled “Riches a Poem.” His financial situation often precarious, in 1741 he would appeal to the public for support at a benefit performance of Double Falshood.

—Allison Muri, September 2018, revised July 2022

This image is provided courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University Library. Yale University makes digital copies of unrestricted public domain collections available for use without limitations through the University’s electronic interfaces (Yale University Policy on Open Access to Digital Representations of Works in the Public Domain from Museum, Library, and Archive Collections). The copyright term for this image is assumed to be expired.