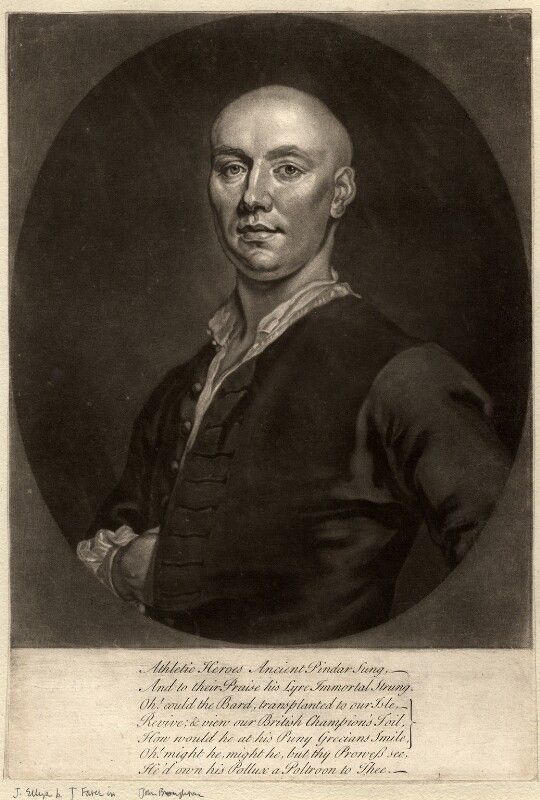

John Broughton (1704? – 8 January 1789)

Allison Muri, University of Saskatchewan

July 2022; revised August 2024

John (Jack) Broughton, pugilist, was born ca. 1704, probably in London. Apprenticed at a relatively late age in 1723 to a Waterman, he was assigned to a Lighterman (one who loads, unloads, and transports cargo on a lighter, a boat for carrying merchandise) on the same day (Tony Gee, ODNB). He plied at Hungerford Stairs and gained his freedom in 1729 or 30. Soon afterwards he turned to pugilism, which in Broughton's day entailed fighting with bare fists and not with boxing gloves or the "mufflers" he would provide to his students to "secure them from the Inconveniency of black Eyes, broken Jaws, and bloody Noses" (Proposals for Erecting an Amphitheatre for the Manly Exercise of Boxing, 1743, p. 4). He rose to become the predominant fighter of his day. He would become one of the king's bodyguard of the Yeomen of the Guard, an appointment he held until his death.

In 1734 he identified himself as "John Broughton, at the Sign of the Crown in St. James's Market, Waterman and Lighterman" (Daily Journal, November 23). In 1743 he opened his "New Amphitheatre," for which he had written an ambitious proposal early in the year as "John Broughton, Professor of Athletics." The amphitheatre was advertised as located at the “back of the late Mr. Figg’s” or “near the late Mr. Figg’s, in Oxford Road.” He did not build a boxing theatre in nearby Hanway Street, Oxford Street, in 1742 as Pierce Egan in his Boxiana (1812) claims.

As did other champions of his day, Broughton cultivated his fame and his persona as a fighter through the newspapers:

This Day is publish'd, Price 6 d,

A Political Battle Royal: Designed for Broughton's new Amphitheatre. A mock Print. Giovanni Elliso, Pinxit. Jack Broughton, Sculpit.—Westminster Journal or New Weekly Miscellany 70, Saturday, March 26, 1743

At Broughton's new Amphitheatre, in Oxford-Road, the back of the late Mr. Figg's, this Day being the 28th instant, will be exhibited the true Art of Boxing, between the following Champions, viz.

I James Farrell, from the County of Cornwall, having gained the good Opinion of my own Countrymen by my Behaviour in many terrible Battles, and never defeated in any; being emulous of future Conquests, and hearing the Fame of the celebrated Thomas Smallwood, and desirous to increase my Character, invite him to fight me at the Place above for Ten Pounds, when I doubt not but to obtain the general Applause of the Spectators, and convince him that the Superiority of Manhood belongs to James Farrell.

I Thomas Smallwood accept the Challenge, and will not fail to meet and fight him for his Sum, and convince him that he is in an Error. Thomas Smallwood.

There will be several By Battles as usual, particularly one between Jack Smallwood and Richard Smallman, for Two Guineas.

The Doors will be open'd at Ten, and the Masters mount at Twelve.—Daily Advertiser 4039, Wednesday, December 28, 1743

The Amphitheatre did not take long to attract criticism:

We hear that the Boxing Amphitheatre will soon be suppressed by the Bench of Justices, as it is thought to contribute to the Nursery of a great Number of loose, idle, and disorderly People.

—General Advertiser 5081, Thursday, February 8, 1750

Following an incident in 1750 where he and pugilist Jack Slack, a butcher originally from Norfolk, had committed "personal Abuse to each other at the late Election at Brentford," Broughton came out of retirement as a pugilist to fight Slack at the Amphitheatre in Oxford Road, "when, no doubt, it will be attended with much Loss of Blood, if not Life," according to one newspaper announcement, which gave odds of six to one in favour of Broughton (Whitehall Evening Post, 7–10 April 1750).

Yesterday there was a Boxing-Match at Broughton's Amphitheatre in Oxford Road, between Stephen Loomer and Charles Johnson; the Battle lasted about a Quarter of an Hour, when Loomer gave out. At the same Time John Slack went upon the Stage and offer'd to fight Broughton immediately for 20 Guineas, agreeable to his Challenge, which he threw upon the Stage: upon which Broughton told the Gentlemen present, that he would gladly embrace the Opportunity, but that, as Slack had been in Keeping some Months, and himself not immediately prepar'd for fighting, declin'd the Battle; but, at the same Time, offer'd Slack ten Guineas to meet him there and fight him as that Day Month, which Slack accepted of.

—London Evening Post 3493, March 13–15, 1750

The fight took place on 11 April. It would be Broughton's final match. An advertisement for the fight claimed he had had an "uninterrupted Course of Victories" for the previous twenty-four years (Gee), but Broughton had not fought for several years and in just over fourteen minutes he was defeated by Slack. Broughton's defeat resulted in significant controversy. His patron, William Augustus the Duke of Cumberland was said to have lost a significant amount in bets placed on Broughton, and accounts in the papers and satires in prints made damning accusations of cheating.

The great Boxing-Match between Broughton and Slack the Butcher, which has been the Subject of so much Conversation among the modern English Heroes of all Ranks, was fought yesterday Morning, when Broughton was fairly beat in 14 Minutes and 11 Seconds. The House was full very early. The first two Minutes the Odds for Broughton were twenty to one; but Slack soon recovering himself chang'd the Betts by closing the Eyes of his Antagonists, and following him close at the same Time, gain'd a compleat Victory, to the no small Mortification of the Knowing Ones, who were finely let in. Before they began Broughton gave Slack the ten Guineas to fight him, according to his Promise, which Slack immediately betted against 100 Guineas offer'd by a Gentleman against him.—The Money receiv'd at the Door amounted to 130 l. besides 200 Tickets at a Guinea and Half a Guinea each.—So that it's thought, what with the Money receiv'd at the Door, that for the Tickets, (as they fought for the whole House) and the Odds Slack took, that he did not clear less than 600 l.

—London Evening Post 3505, April 10–12, 1750

The Bruiser Bruis'd: Or, the Knowing-Ones Taken-in

Vain-Glory shou'd be foil'd, & Coxcombs known:

The Knowing Ones here thought to Gull the Town.

In Diff'rent Modes are England's Fools display'd;

Some Strut in Rags, some flutter in Brocade.

Those, Who, abroad the Sword durst never use;

At Home their boasted Courage will abuse:

They run From Quiberon and Fontenoy,

But Here each other cowardly destroy.

The Prince of Bruisers, by Vain-Glory hurt,

Has laid at last, his Conquests in the Dirt:

Where's now thy Cestus? All thy Triumph's gone,

Mourn for thy Motto, and thy Sign pull down.

According to Act 1750 Printed & Sold at E. Griffins Map & Printshop, next the Globe Tavern in Fleetstreet Prices 6.d plain Colour'd 2.s—Satirical print, 1750, British Museum number 1868,0808.3904

Sl-k Triumphant or B-ck-se in Tears for his Masters Defeat

Ye Bruisers of the Town appear,

And mourn your Glory sinking here

Long have ye storve by various Arts

To trick the World and bost your Parts

Your Puffs in ev'ry Paper flew

And heedless Gulls to Slaughter drew

When Gaming Drinking or your W—re

Had render'd ye quite low and poor

And Pockets cou'd not shew a Souse

Then make a match—Fight for the House

First you shall beat—and next I'll win

Get the Fools Pence and then we'll grin

Thus have y oft, when o'er your Bowls

In private talk'd ye jovial Souls!

Dame Preston first the sport begun

And Bandy-Stokes then push'd it on

To mention all such Heroes known

Wou'd mark ye all the Scum o' th' Town

In its first Rise 'twas scorn'd as mean

But our late Boxer chang'd the Scene

Eger of Fame and full of Pelf

Erects a stage to beat himself

What Whim possesd his Silly Brain

To make him mount that Stage Invain.—Satirical print, ca. 1750, British Museum number 1868,0808.3907

The authorities seized on the opportunity to shut the amphitheatre down, as reported in variations on the theme in several papers:

We hear that the Boxing Theatre in Tyburn Road will soon be suppressed by the Bench of Justices, as it is thought to contribute to the Nursery of a great number of loose, idle, and disorderly People.

—Whitehall Evening Post 779, February 5–7, 1751

We hear the Boxing Amphitheatre will soon be suppressed, on a Supposition (not a chimerical one) that it may become a Nursery for Villainy, &c.

—Old England 359, Saturday, Feb. 9, 1751

We hear that the Boxing Amphitheatre will soon be suppressed by the Bench of Justices, as it is thought to contribute to the Nursery of a great Number of loose, idle, and disorderly People.

—Penny London Post or The Morning Advertiser 1380, February 8–11, 1751

The Amphitheatre continued to operate in 1752, however, with reports in the news of its unsavory presence:

Yesterday Slack defeated the Chairman at Broughton's Amphitheatre in about three minutes, in the Presence of a dignified and crowded Audience Just before the Heroes mounted the Stage, there was an Alarm given, the Gallery was falling down, which put the Spectators into great Confusion.

—London Evening Post 3793, February 8–11, 1752

Yesterday at Broughton's bruising Amphitheatre, there was a very obstinate Battle between Faulkener, the Cricket Player, and Smallwood. Before the Champions mounted, the Odds were five, six and Seven to One on Smallwood's head; but after the Engagement had lasted fourteen Minutes and a Half, Smallwood was so severely handled, that he was carried senseless off the Stage, and the knowing ones were deeply taken in. There was a full House to the great Encouragement of the Gentlemen Bruisers.

—London Daily Advertiser 352, Thursday, April 16, 1752.

By 1754, the authorities had their way, and boxing enthusiasts could only lament their loss:

I cannot but lament the cruelty of that law, which has shut up our Amphitheatres: and I look upon the professors of the noble art of Boxing as a kind of disbanded army, for whom we have made no provision. The mechanics, who at the call of glory left their mean occupations, are now obliged to have recourse to them again; and coachmen and barbers resume the whip and the razor, instead of giving black eyes and cross-buttocks. I know a veteran that has often won the whole house, who is reduced, like Belisarius, to spread his palm in begging for a half-penny. Some have been forced to exercise their art in knocking down passengers in dark alleys and corners; while others have learned to open their fists and ply their fingers in picking pockets. Buckhorse, whose knuckles had been used to indent many a bruise, now clenches them only to grasp a link; and Broughton employs the muscles of his brawny arm in squeezing a lemon or drawing a cork. His Amphitheatre itself is converted into a Methodist Meeting-house! and perhaps (as laymen are there admitted into the pulpit) those very fists, which so lately dealt such hearty bangs upon the stage, are now with equal vehemence thumping the cushion.

—Connoisseur 30 (Collected Issues), Thursday, August 22, 1754

In 1768–9 Broughton was implicated in hiring a number of thugs to appear in Brentford during the election of one of the candidates, Sir William Beauchamp Proctor, for Knight of the Shire for the county of Middlesex. One witness testified that the men sported "Proctor and Liberty" labels on their hats and told him they could not vote but the bludgeons in their hands were just as good, and if Serjeant Glynn were to get the advantage, they swore "By God we will have his Blood" (Public Advertiser, 14 December, 1768). Two men, one of them hired by Broughton according to court testimony, were charged for the murder of another in the ensuing riot. They were found guilty but later pardoned, not without controversy. The papers reported regularly on the trial and its outcomes, with increasing outrage at the role of Broughton and others in the events of the riot. On 10 July, 1769, the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser reported that Broughton, along with the hired rioters McQuirk and Balse, had been arraigned under consideration for exportation, as "Assistants in the Butchery." Broughton, however, was still employed as a Yeoman of the Guards "in the houshold service of his Majesty" two years later, complained an editorial in the Middlesex Journal (March 26–28, 1771).

Broughton died in 1789 at the age of eighty-four or eighty-five. He was buried in the west cloister of Westminster Abbey on 21 January in a wood coffin beside his wife Elizabeth, who had died 7 December 1784, at the age of fifty-nine (Westminster Abbey). The Morning Herald featured an affectonate eulogy:

The admirers of the fashionable science of Boxing should now put themselves in deep mourning, for on Thursday the famous Mr. John Broughton, whose skill in that branch of modern education will be ever recorded in the annals of Athletics, concluded his earthly career in the eighty-fifth year of his age, at this house in Walcot-place, Lambeth.

It is generally acknowledged by amateurs in this science, and even its most distinguished professors, that Broughton carried the theory and practice of it to the highest point of perfection; and that what his genius could not accomplish, it is vain for human abilities to attempt.

Broughton’s history is speedily related. He served an apprenticeship to a waterman, and when he was able to follow his business on his own account, generally plyed at Hungerford-stairs. Upon some accidental difference with a brother of the oar, which was decided at once by a manly appeal to the fist, it was soon found he possessed a genius far beyond the grovelling province in which it was confined, and therefore leaving his boat to sink or swim, he assumed the dignified rank of a Public Bruiser, and in this character was patronized by some of the first men in the kingdom.

Supported by this patronage, which his powerful abilities amply deserved, he instituted a pugilistic academy in Tottenham-court-road, where his pupils, and those who felt a laudable thirst after fame, had an opportunity of signalizing their dexterity and prowess before the highest and most polite audience that the nation could supply.

In this illustrious situation, Broughton frequently astonished his scholars and the public, by a display of his own pre-eminence, and was always triumphant, till his sad contention with Slack, in which, to adopt the language of his seminary, he came off second best.

After this lamentable failure, which, however, contributed more to the present mortification, than the consequent disgrace of Broughton, he retired into private life, subsisting very comfortably upon the produce of his hands, and his situation as one of the Yeomen of the Guards.

It should have been mentioned before, that Broughton was highly in favour with the late Duke of Cumberland, and attended one of his military expeditions on the Continent, where, on being shewn a foreign regiment of terrific appearance, the Duke asked him if he thought he could beat any of the men that composed it—upon which Broughton replied, “Yes, please your Royal Highness, the whole corps, with a breakfast between every battle.”

Such is the brief story of our British Milo.—The Morning Herald, Tuesday, January 13, 1789

The best biography of John Broughton is by Tony Gee, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/3586.

Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900)

BROUGHTON, JOHN (1705–1789), pugilist, was born in 1705, but there is no record of his birthplace, although it may be assumed to have been London. As a boy he was apprenticed to a Thames waterman, and, when at work on his own account, he generally plied at Hungerford Stairs.

He is usually considered as the father of British pugilism, combats, previous to his appearance, having been chiefly decided either by backsword or quarterstaff on a raised stage. Accident settled his future career. Having had a difference with a brother waterman, they fought it out; and he showed so much aptitude for the profession which he afterwards adopted, that he gave up his boat and turned public bruiser, for which his height (5 ft. 11 in.) and weight (about 14 stone) peculiarly fitted him.

He attached himself to George Taylor's booth in Tottenham Court Road, and remained there till 1742, patronised by the élite of society, and even royalty itself in the person of the Duke of Cumberland, who procured him a place, which he held until his death, among the yeomen of the guard. But the duke ultimately deserted him. Broughton fought Slack on 11 April 1750, and the duke backed his protégè the champion, it is said, for 10,000l. Broughton lost the fight, having been blinded by his adversary, and the duke never forgave him for being the cause of his loss of money. After this battle Broughton's career as a pugilist was ended. In 1742 he quarrelled with Taylor, and built a theatre for boxing, &c., for himself in Hanway Street, Oxford Street. There he performed until his retirement, when he went to live at Walcot Place, Lambeth. He resided there until his death, on 8 Jan. 1789. He amassed considerable property, some 7,000l., and dying intestate, it went to his niece. He was buried on 21 Jan. 1789 in Lambeth Church, his pall-bearers being, by his own request, Humphries, Mendoza, Big Ben, Ward, Ryan, and Johnston, all noted pugilists. His epitaph was as follows:

Hic jacet

Iohannes Broughton,

Pugil ævi sui præstantissimus.

Obiit

Die Octavo Ianuarii,

Anno Salutis 1789,

Ætatis suæ 85.

[Capt. Godfrey's Treatise upon the Useful Science of Self-Defence, 1747; Pugilistica; Boxiana; Fistiana; Morning Post, January 1789.]

J. A.