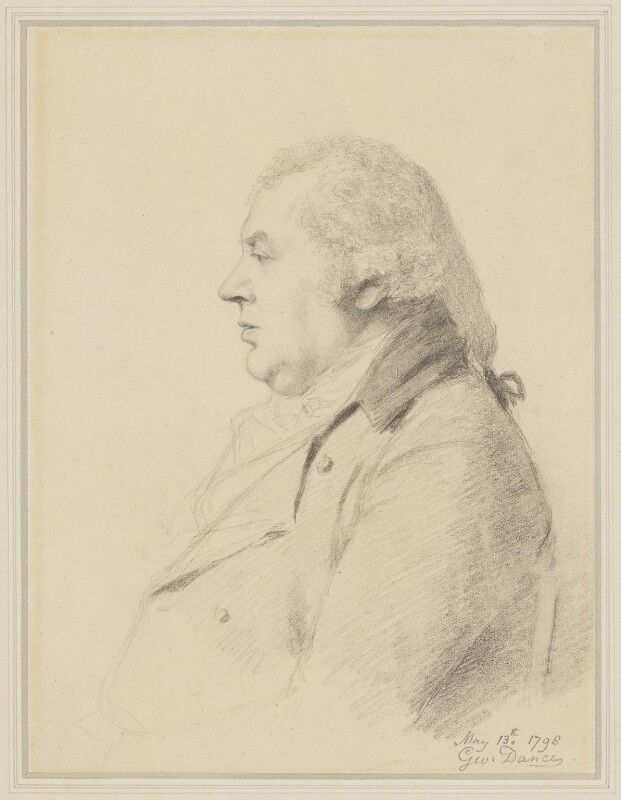

William Shield (1748–1829)

Paul F. Rice, Memorial University of Newfoundland

December 2022

William Shield was a violinist, violist, theorist, and composer.

Shield was born in Swalwell, near Newcastle upon Tyne, the son of a music teacher. He learned the rudiments of music from an early age but, when his parents died, the eight-year-old Shield was forced to accept an apprenticeship to a local boat builder. Shield continued to learn the violin and was able to study music with Charles Avison (1709–70) in Newcastle. After Avison’s death, Shield began to play violin in a local theatre orchestra and to lead concerts in Scarborough and Durham. Success in these ventures led Shield to venture to London in 1772 where he soon found employment as a violinist at the King’s Theatre (the home of Italian opera in London). The following year, he took over the position of principal violist in the theatre’s orchestra, remaining there for the next eighteen years. As Roger Fiske writes, “much of his musical education was picked up from what he heard there in operas by Sacchini, Paisiello, and others” (English Theatre Music in the Eighteenth Century, 1986).

Shield’s first theatrical success was with The Flitch of Bacon in 1778, an afterpiece containing fourteen numbers. Typical of Shield’s output, the work is a pastiche ballad-opera with spoken dialogue; nine of the numbers are by Shield, with the others borrowed from disparate sources, including English madrigals, folksong, and an aria from Giordani’s La vera constanza. In 1784, Shield became a house composer for the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden. With the exception of the 1791–92 season when he was abroad, Shield retained this position until 1797. Shield’s ability to write in a variety of styles was quickly recognized. He was adept in creating pseudo-Irish and Scots music, in addition to composing music reminiscent of British folk music and Italian opera. This ability found an outlet in the music that he composed for John Johnstone (1749–1828), the self-taught Irish tenor who was known for his very high falsetto notes. Johnstone made his Covent Garden debut in 1783, at which time he enjoyed an enormous success, both for his voice and his engaging stage personality. While his strong Irish accent limited the number of parts available to him, Shield tried to find an appropriate part for Johnstone in his works, whenever possible. That Shield was appointed to Covent Garden as a resident composer in 1784 should not surprise, given the runaway success of his Rosina in 1782. This opera was given over 2000 London performances by 1800, and is the only opera by Shield that survives in full score. An excellent modern recording also exists. The opera is again a pastiche, and Fiske notes that “of the eighteen vocal items, six have identifiable ballad tunes and another six are composed more or less in ballad style” (English Theatre Music in the Eighteenth Century, 1986). What makes Shield’s treatment of the ballad tradition remarkable is that all of the characters sing a variety of musical styles, as opposed to having the rustics performing the ballad tunes, while the aristocrats sing more complicated music. Shield’s strengths lay in contributing appropriate music to charming pastoral works and comic pieces. These were not necessarily the qualities that would serve him well as world events became darker.

Following the fall of the Bastille in Paris, the London theatres took great interest in presenting topical works based on the growing unrest in France and the perceived dangers that the overthrow of the French monarchy might pose to Britain. Shield contributed music to a variety of patriotic works, beginning with The Crusade in 1790, which was followed in that same year by The Picture of Paris, Taken in the Year 1790. The latter work was described as a pantomime in two acts which dealt with the Champ de Mars or the first anniversary of the fall of the Bastille. The plot was a curious mix of harlequinade and drama, but it gave ample scope to Shield’s talents. He made use of the French revolutionary song “Ça ira,” a daring choice, but something which gave an air of authenticity and immediacy to the score. The score was again a pastiche, and the ensembles were borrowed from Amphion, an opera by Johann Gottlieb Naumann (1741–1801). John Johnstone played a significant part in the production and Shield afforded him several characteristic “Irish” airs. One of Shield’s most popular works was Hartford Bridge; or, The Skirts of the Camp which received 48 performances between November 1, 1792, and May 20, 1800. Composed at a time when war between France and Britain had not yet begun, the work is a two-act farce which has as its backdrop the military training exercises at Bagshot Heath. Shield’s music is wide ranging and includes airs with military overtones, love songs and duets, and comic songs. Much of the score appears to have been composed by Shield, although the London newspapers reported that music by Antonio Sacchini (1730–86) and Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) could be found therein. Four examples from this opera have been recorded on CD: the overture, two arias and a duet.

Once France declared war against Britain in January of 1793, the plots of the patriotic pieces could no longer be farcical and light-hearted. Shield soldiered on, contributing music to The Relief of Williamstadt (1793), To Arms; or, The British Recruit (1793), Sprigs of Laurel; or, Royal Example (1793), Netley Abbey (1794), Arrived at Portsmouth (1794), and The Death of Captain Faulknor; or British Heroism (1795). All had pastiche scores. Not all proved to be popular, and some received only a few performances. Netley Abbey was the most successful, although the plot was judged to be inferior to that of Hartford Bridge. Still, the two-act afterpiece received thirty-two performances before 1800. Its score was well appreciated, and W.T. Parke (1761–1847) remembered the work fondly thirty-six years after the premiere:

In this piece Facet has a sea song, ‘Blue Peter,’ in which was introduced ‘the boxing of the compass’ which, from the merit of the music (by Shield) and the effective manner in which it was sung, was loudly encored. Mrs. Martyr, as a sailor boy, in the song ‘Yo! Heave ho!’ composed by me, was greatly applauded; and Incledon sang the old song, ‘On board the Arethusa,’ admirably. The music of this piece, composed by Paesiello, Baumgarten, Dr. Arne, myself and Shield was very effective, and had a long run.—Parke, Musical Memoirs; comprising an Account of the General State of Music in England, 1830.

By this time, however, tension was mounting between Shield and the management of the Covent Garden theatre. The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, had mounted several spectacular works with scores arranged by Stephen Storace (1762–96) that were perceived to be more exciting and in keeping with the times. Shield finally broke with Covent Garden in 1797 and turned his attention to theoretical matters. In 1817, he became Master of the King’s Music, and he wrote his final court ode the following year. Shield’s output in instrumental genres is not large, but includes six string quartets, six string trios and duets for two violins. He is buried in the same grave as the violinist and impresario Johann Peter Salomon in the south cloister of Westminster Abbey, London.