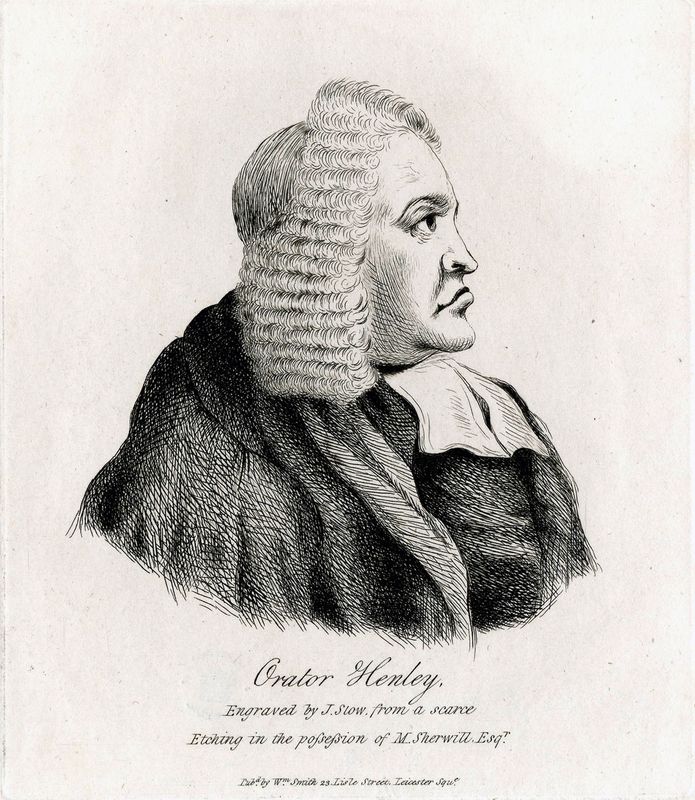

John Henley (1692–1756)

Note: the 19th- and early-twentieth-century biographies below preserve a historical record. A new biography is forthcoming.

Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900)

HENLEY, JOHN (1692–1756), generally known as Orator Henley, an eccentric London preacher, was born 3 Aug. 1692 at Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire, where his father, the Rev. Simon Henley, had succeeded John Dowell, his grandfather by his mother's side, as vicar of the parish. Henley was educated at Melton Mowbray grammar school, and privately at Oakham, Rutlandshire, where he devoted special attention to Greek and Hebrew. He entered St. John's College, Cambridge, in 1709, graduated B.A. in 1712, and M.A. in 1716. The method of teaching prevalent in the university he found to be unduly restrictive. He was ‘uneasy that the art of thinking regularly on all subjects and for all functions was not the prevailing instruction.’ Owing to his impatience of the systems ‘ready carved out for him’ he ‘incurred the danger of losing interest in his studies, as well as incurring the scandal of heterodoxy and ill principle.’ From an early period he seems to have recognised that he had a special vocation for introducing new methods of conveying both secular and religious knowledge. He did not profess to be a reformer, except as regards methods, and was destitute of the intellectual ability necessary to enable him to distinguish himself as an opponent of current creeds. His chief gift, apart from his pompous but effective elocution, was a ready wit which gained much of its piquancy from contrast with the otherwise grave and solemn character of his prelections. On 3 Feb. 1712, while an undergraduate at Cambridge, he wrote, under the name of ‘Dr. Quir,’ a witty letter to the ‘Spectator’ on Cambridge matters. In the same year he was appointed assistant in the free school of Melton Mowbray, and shortly afterwards he succeeded as head-master. Here he established the practice of ‘improving elocution by the public speaking of passages in the classics morning and afternoon, as well as orations.’ Shortly after graduating M.A. in 1716 he was ordained, and for some years held a curacy in his native town, but in 1721 he came to London, where he was reader at the church of St. George the Martyr. He also obtained a lectureship in the city, where, according to his own account, he ‘preached more charity sermons, was more numerously attended, and raised more money for the poor children than any other preacher.’ But his eccentricities were too patent to permit him to retain his posts in London. Much against his inclination he was compelled to retire, about 1724, to the living of Chelmondiston in Suffolk. ‘His popularity and his enterprising spirit, and introducing regular actions into the pulpits were the true causes,’ he asserted, ‘why some obstructed his rising in town from envy, jealousy, and a disrelish of those who are not equal for becoming complete spaniels.’

Recognising that his gifts were not properly appreciated within the church, Henley resolved to break off his connection with it. In 1726 he rented rooms in Newport Market above the market-house. Here every Sunday he preached a sermon in the morning, and in the evening delivered an oration on some special theological theme; and lectured on Wednesdays on ‘some other science.’ He struck medals to distribute as tickets to subscribers, engraved with a star rising to the meridian, with the motto ‘Ad summa,’ and below ‘Inveniam viam aut faciam.’ He advertised on Saturdays the subject of his next oration in mysterious terms to arouse curiosity and draw a crowd. On one occasion a large audience of shoemakers assembled, enticed by the promise that he would show them a new and speedy method of making shoes. This, he explained in the course of his oration, was by cutting the tops off boots. On another occasion he delivered a ‘butchers' lecture,’ lauding the trade extravagantly. Henley claimed to be the ‘restorer of eloquence to the church.’ Pope writes of him in the ‘Dunciad,’ iii. 205–6:—

Oh great Restorer of the good old Stage,

Preacher at once, and Zany of thy age!

Henley's ritual was gaudy and elaborate. He preached in a pulpit, ridiculed by Pope as ‘Henley's guilt tub’ (Dunciad, ii. 2), which blazed in gold and velvet. In his service book he sometimes printed his creeds and doxologies in red letters. His methods of oratory are described in his own writings on the subject.

Henley did not confine himself to ecclesiastical duties. As early as 1724 he had joined Curll, the pirate publisher, in a correspondence with Sir Robert Walpole offering to suppress a libellous attack on the ministers by Mrs. Manley. He wrote to Walpole arranging an interview, 4 March 1723–4, and added, ‘my intentions are both honourable and sincere, and I doubt not but they will meet with a suitable return’ ( Notes and Queries, 2nd ser. ii. 443). In behalf of Walpole he was, in 1730, employed, at a salary of 100l., to ridicule the arguments of the ‘Craftsman,’ the opposition journal, in a new periodical called the ‘Hyp Doctor,’ which appeared at intervals from 15 Dec. 1730 to 2 Dec. 1739. Here he assumed many pseudonyms, such as Sir Isaac Ratcliffe of Elbow Lane, Alexander Ratcliffe, Jonadab Swift, Bryan Bayonet, &c. On 4 Dec. 1746 he was apprehended on a charge of ‘endeavouring to alienate the minds of his Majesty's subjects from their allegiance by his Sunday harangues at his Oratory Chapel,’ but in a few days was admitted to bail, and never underwent a trial. In 1747 he engaged in a public controversy with Foote on the stage of the Haymarket Theatre, displaying remarkable proficiency in low buffoonery. Since 1729 he had been established in Lincoln's Inn Fields near Clare Market. He died on 14 Oct. 1756.

Henley published: 1. ‘Esther, Queen of Persia, an Historical Poem in four books,’ 1714; there is much tame or turgid writing in this poem, but it is in parts oratorically effective. 2. ‘The Complete Linguist with a Preface to every Grammar,’ London, 1719–21; seven numbers only appeared, on Spanish, French, Italian, Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and Chaldee. 3. ‘Apotheosis, a Funeral Oration sacred to the Memory of John, Duke of Marlborough,’ London, 1722. 4. ‘The History and Advantages of Divine Revelation, with the honour that is due to the Word of God, especially in regard to the most perfect manner of delivering it, formed on the Ancient Laws of Speaking and Action, being an Essay to restore them,’ 1725. 5. ‘An Introduction to an English Grammar,’ 1726. 6. ‘The Primitive Liturgy for the Use of the Oratory,’ 1726; 4th edit., 1727. 7. ‘Letters and Advertisements,’ 1727. 8. ‘The Appeal of the Oratory and the First Ages of Christianity,’ 1727. 9. ‘The Art of Speaking in Public,’ 1727. 10. ‘Oratory Transactions, No. 1,’ 1728; containing, in addition to a ‘general preface,’ a ‘Biography of Mr. Henley,’ professedly by A. Welstede, but evidently by Henley himself, ‘A Defence of the Oratory against Objections,’ an ‘Idea of what is taught in the Weekday Academy,’ and ‘Plans and Rules of the Conferences and Disputations,’ and other papers. 11. ‘Oratory Transactions, No. 2,’ 1729. 12. ‘Conflicts of the Deathbed,’ 1729. 13. ‘Cato Condemned,’ 1730. 14. ‘Light in a Candlestick,’ 1730. 15. ‘Samuel Sleeping in the Tabernacle,’ a pamphlet against Dr. S. Chandler, 1730. 16. ‘The Orators' Miscellany,’ 1731. 17. ‘Deism Defeated and Christianity Defended,’ 1731. 18. ‘The Origin of Pain and Evil,’ 1731. 19. ‘A Course of Academical Lectures,’ 1731. 20. ‘Select Discourses on Several Subjects,’ 1737. 21. ‘The Orators' Magazine,’ 1748. 22. ‘Law and Arguments in Vindication of the University of Oxford,’ 1750. 23. ‘Second St. Paul and Equity Hall,’ 1755. He wrote two ‘Spectator’ papers—Nos. 94 and 578. He also edited ‘The Works of John Sheffield, Duke of Buckingham,’ 1722; and translated 1. Aubert de Vertot's ‘Critical History of the Establishment of the Bretons among the Gauls,’ 1722. 2. Pliny's ‘Epistles and Panegyrics,’ 1724. 3. Montfaucon's ‘Travels in Italy,’ 1725. His original manuscripts and manuscript collections were sold by auction, 11–15 June 1759. About fifty volumes of his lectures, in his own hand, are now in Brit. Mus. MSS. Addit. 10346–9, 11768–801, 12199, 12200, 19920–4. Other volumes by him are in the Guildhall Library, London. Henley is the subject of two well-known humorous plates by Hogarth—one, ‘The Christening of the Child,’ the other ‘The Oratory.’

[Nichols's Leicestershire, ii. 259–*261, 423; Nichols's Anecdotes of Hogarth; Disraeli's Calamities of Authors; Dibdin's Bibliomania; Notes and Queries, 1st ser. xii. 44, 88, 155, 2nd ser. ii. 443, v. 150; Pope's Works, ed. Elwin and Courthope; Retrospective Review, xiv. 216.]

T. F. H.

Encyclopædia Britannica 11th edition (1911)

HENLEY, JOHN (1692–1759), English clergyman, commonly known as “Orator Henley,” was born on the 3rd of August 1692 at Melton-Mowbray, where his father was vicar. After attending the grammar schools of Melton and Oakham, he entered St John’s College, Cambridge, and while still an undergraduate he addressed in February 1712, under the pseudonym of Peter de Quir, a letter to the Spectator displaying no small wit and humour. After graduating B.A., he became assistant and then headmaster of the grammar school of his native town, uniting to these duties those of assistant curate. His abundant energy found still further expression in a poem entitled Esther, Queen of Persia (1714), and in the compilation of a grammar of ten languages entitled The Complete Linguist (2 vols., London, 1719–1721). He then decided to go to London, where he obtained the appointment of assistant preacher in the chapels of Ormond Street and Bloomsbury. In 1723 he was presented to the rectory of Chelmondiston in Suffolk; but residence being insisted on, he resigned both his appointments, and on the 3rd of July 1726 opened what he called an “oratory” in Newport Market, which he licensed under the Toleration Act. In 1729 he transferred the scene of his operations to Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Into his services he introduced many peculiar alterations: he drew up a “Primitive Liturgy,” in which he substituted for the Nicene and Athanasian creeds two creeds taken from the Apostolical Constitutions; for his “Primitive Eucharist” he made use of unleavened bread and mixed wine; he distributed at the price of one shilling medals of admission to his oratory, with the device of a sun rising to the meridian, with the motto Ad summa, and the words Inveniam viam aut faciam below. But the most original element in the services was Henley himself, who is described by Pope in the Dunciad as

“Preacher at once and zany of his age.”

He possessed some oratorical ability and adopted a very theatrical style of elocution, “tuning his voice and balancing his hands”; and his addresses were a strange medley of solemnity and buffoonery, of clever wit and the wildest absurdity, of able and original disquisition and the worst artifices of the oratorical charlatan. His services were much frequented by the “free-thinkers,” and he himself expressed his determination “to die a rational.” Besides his Sunday sermons, he delivered Wednesday lectures on social and political subjects; and he also projected a scheme for connecting with the “oratory” a university on quite a utopian plan. For some time he edited the Hyp Doctor, a weekly paper established in opposition to the Craftsman, and for this service he enjoyed a pension of £100 a year from Sir Robert Walpole. At first the orations of Henley drew great crowds, but, although he never discontinued his services, his audience latterly dwindled almost entirely away. He died on the 13th of October 1759.

Henley is the subject of several of Hogarth’s prints. His life, professedly written by A. Welstede, but in all probability by himself, was inserted by him in his Oratory Transactions. See J. B. Nichols, History of Leicestershire; I. Disraeli, Calamities of Authors.