Thomas Augustine Arne (1710–1778)

Paul F. Rice, Memorial University of Newfoundland

August 2022

Thomas A. Arne (1710–78), composer, performer and teacher, was born in King Street, Covent Garden, on March 12, 1710. He was the son of an upholsterer and undertaker. With the help of the violinist Michael Festing, Arne overcame parental opposition to his musical aspirations to achieve a significant career in eighteenth-century London and Dublin. It was Festing who taught Arne the violin and helped Arne’s father become reconciled with his son’s musical aspirations. The elder Arne had wanted his son to pursue a legal career, an option unavailable to the younger Arne once he decided to adopt his mother’s Catholic faith. This choice also affected his musical career. As a Catholic, he was prevented from accepting positions at court or in the Anglican Church. Furthermore, he would have faced the prejudice against British performers and composers held by the influential aristocratic class. Continental tastes held sway in the elite London concert series, such as that run by J.C. Bach (1735–82) and K.F. Abel (1723–1787) and in the homes of the social elite. Charles Dibdin (1745–1814) writes that “had not Arne all his life been discouraged, and Handel considered as another Apollo, the fame of the Englishman would have exceeded that of the German” (The Musical Tour of Mr. Dibdin, 1788).

Denied access to the highest realms of musical achievement in the capitol, Arne made his career in the theatres of London and Dublin as a composer, while also composing a variety of vocal works for the summer concerts of the London pleasure gardens. His songs and ballads performed at the pleasure gardens were published in volumes at the end of the summer seasons and gave much pleasure in the homes of Georgian England. Charles Burney writes that these works “had improved and polished our national taste,” adding further that Arne had “formed a new style of his own” (A General History of Music, 4, 1789). In addition, Arne contributed music to nearly one hundred stage works, including incidental music, masques, English operas, and two serious works in the Italianate style: Artaxerxes (1762) and L’olimpiade (1765). Outside of theatrical music, Arne composed 2 Masses, 4 symphonies, 6 concerti, 2 oratorios, 5 Italian odes, keyboard music and chamber music, and numerous songs and cantatas.

Arne began writing for the theatre in 1732 and in March of 1733, his Rosamond was produced successfully at the Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre with a cast that included his sister Susannah and his younger brother Richard, both of whom he had taught to sing. Susannah married the playwright Theophilus Cibber (the son of Colley Cibber) in 1734 and took up a contract at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Arne began to supply music for that theatre and this did much to bring him to prominence. In 1737, Arne married the talented soprano Cecilia Young (1712–89) who had previously performed in Handel’s oratorios and Italian operas. Mrs. Arne, as she was now known, performed in some of Arne’s earliest successes at the Drury Lane theatre, including Comus (1738) and The Judgement of Paris (1742). It was the production of Alfred (1740) at Cliveden, the home of Frederick, Prince of Wales (1707–51), where Arne became introduced to those opposed to the politics of Robert Walpole (1676–1745) in his joint roles of First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer. It was commonly believed that Walpole abused his position for personal gain and exerted undue influence over the court of George II. A loosely structured group of intellectuals, politicians, and artists joined forces in the “Politics of Opposition” against Walpole and the king. This group gravitated to the writings of Henry St. John, Viscount Bolingbroke (1678–1751) whose liberal ideology in The Idea of a Patriot King was set down in 1738. Although initially much circulated privately, the work’s first authorized publication came only in 1749, carrying a dedication to Prince Frederick who was clearly being groomed to fit Bolingbroke’s idea of kingship. The libretto for Alfred by David Mallet (1701/02–65) and James Thomson (1700–48) presented an allegory of the Prince of Wales as Alfred the Great (849–99). Thus, when Arne accepted the commission to compose the music for Alfred in 1740, it came with political associations. Such beliefs would have been attractive to a young composer who had every reason to believe that he would never find a place in the upper echelons of the musical establishment under George II. Today, the political agenda in the libretto is less evident and only the patriotic air “Rule Britannia” is heard today.

Arne enjoyed much success at the Drury Lane theatre, but his working relationship became strained when the management was taken over in 1747 by David Garrick (1717–79) and James Lacy (1696–1774). Garrick was an autocrat and politically conservative. A mutiny broke out at the beginning of the 1750–51 season that saw the departure of Arne, his sister Susanna Cibber and leading actors such as Spranger Barry and Margaret [Peg] Woffington for rival theatres. Garrick never really forgave Arne for his desertion, although the relationship was eventually repaired sufficiently that Arne contributed a dozen subsequent works for the Drury Lane theatre. None of these achieved the same level of success as Arne’s work for the rival Covent Garden theatre, however. There, in 1762, Arne enjoyed one of his greatest triumphs when Artaxerxes was produced on February 2nd. Based on a translation of an Italian libretto by Metastasio from 1729 (possibly by Arne), the work was an instant success and was regularly performed well into the nineteenth century. It is occasionally revived in the modern era and arias such as “The Soldier, tir'd of war's alarms” and “Water parted from the Sea” remain concert favourites.

The opportunity to expand Arne’s musical influence in London came about in the mid-1740s when several of the summer pleasure gardens in London introduced vocal music to their concerts. This innovation was not without its difficulties given that the concerts at these locations were presented out-of-doors in an era when amplification did not exist. Venues such as Marylebone and Vauxhall had raised, covered bandstands with pipe organs where instrumental music had previously been performed to an audience who gathered around in the open air. The outlier to this arrangement was the Ranelagh Gardens which boasted a covered structure called the Rotunda. This circular building was large enough so that the audience could promenade while listening to the performance of music. It was also heated which further made it attractive in bad weather. Contemporary reports suggest that the acoustics were little better than at other locations.

Arne began his association with the Vauxhall Gardens in 1745 when his wife was one of three singers hired to perform at the concerts. Thereafter, Arne created a large quantity of vocal music for the Vauxhall concerts. Although there had been public gardens in Vauxhall since 1661, it was not until 1728 when Jonathan Tyers (1702–67) leased the land and transformed the old gardens into a pastoral retreat that they achieved social prominence. Instrumental concerts had begun in 1735, but the introduction of singers of great repute made the location a favourite haunt during the summer months. Frederick, Prince of Wales, was the patron and Jonathan Tyers did much to encourage his attendance at the concerts. The Politics of Opposition were closely connected with the Vauxhall imagery. As David Coke and Alan Borg write:

This rebellion, embodied at Vauxhall in the patronage of Frederick, Prince of Wales, the paintings of William Hogarth and Francis Hayman, the sculpture of Louis François Roubiliac, the music of Thomas Arne and George Frideric Handel, and the designs of Hubert-François Gravelot and George Michael Moser, reflected the libertarian attitudes and enlightened management style of Jonathan Tyers. The brash light-heartedness, the unwillingness to follow rules, the energy, informality and experimentation that were intrinsic to Vauxhall are all typical of the English Rococo; this intoxicating cocktail enhanced every evening’s excitement, and put Tyer’s visitors in the right frame of mind to enjoy themselves, to refresh their spirits and to spend their money. (Vauxhall Gardens: A History, 2011)

Arne would have found himself in congenial company there and his continued composition for the Vauxhall concerts demonstrates the importance that they played in his musical life.

Vauxhall was not the only pleasure garden, however, where Arne’s music was heard and where he actively promoted himself. In the early 1750s, Arne composed music for the concerts at Cuper’s Gardens located in Lambeth, on the south side of the Thames, opposite Somerset House. Several of the singers there had direct contact with Arne: Sibilla Pinto (1720–66) had been a student of Arne’s, while Master George Mattocks (c. 1738–1804) had made his stage debut in Arne’s The Triumph of Peace at Drury Lane in 1749. Arne’s time at Cuper’s Gardens was short-lived, however. The management of the gardens was denied their license to open in 1753, likely because of the reports of pickpockets and wide-spread immorality on the premises.

Daniel Gough introduced vocal singing in the concerts at the Marylebone Gardens in 1744. Once again, Arne’s music was frequently heard there, and he took an active role in those concerts which promoted the singing talents of his “natural” son, Michael (c. 1740–86) during the early 1750s. Michael Arne first appeared in concert at Marylebone on July 5, 1751, and appeared throughout the remainder of season. Thomas Arne also composed music specifically for Anna Maria Falkner’s benefit concert at Marylebone on August 4, 1752. Some of the repertoire that Michael Arne and Miss Falkner performed at Marylebone is represented in Book 3 of Thomas Arne’s Vocal Melody which appeared after the 1751 pleasure-garden season was over.

Arne’s music was much featured in the concerts at Ranelagh during the 1760s. Mollie Sands writes that “for many years his music predominated, and the Ranelagh singers were nearly all connected with him in some way; they were his wife’s relations, or his pupils, or had sung in his operas” (Invitation to Ranelagh, 1946). The concerts of the pleasure gardens became useful tools to promote his musical career. Although it might seem that his presence was ubiquitous in these locations, it was still something of an exaggeration for Hubert Langley to have written that Arne had become the “Director of Music to the Public Gardens” (Dr. Arne, 1938). Still, Arne’s influence over the musical life of London was considerable. If he never achieved a court appointment or had his music performed in the prestigious winter concerts in London, his stage works dominated the London theatres and his vocal music was regularly featured in the concerts of the pleasure gardens and delighted Britons in domestic settings. As such, he was one of the most widely performed and celebrated British composers of his generation.

Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900)

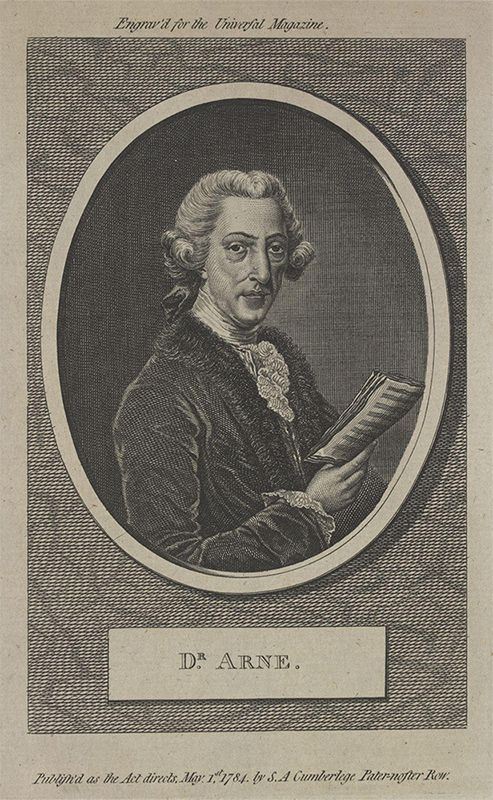

ARNE, THOMAS AUGUSTINE (1710–1778), musical composer, was the son of Thomas Arne, an upholsterer, who lived in King Street, Covent Garden, where his shop was known as the 'Crown and Cushion,' or, according to some authorities, as the 'Two Crowns and Cushion.' Thomas Arne is said to have been the upholsterer with whom the 'Indian kings' lodged, as chronicled in the 'Spectator,' No. 50, and the 'Tatler,' No. 171, and some biographers have identified him with one Edward Arne, who was the original of the political upholsterer of Nos. 156, 160, and 178 of the 'Tatler,' although it is sufficiently obvious that the latter do not refer to the same individual as is mentioned in the earlier numbers. Thomas Arne was twice married; by his second wife, Anne Wheeler, to whom he was married at the Mercers' Chapel in April 1707, he had Thomas Augustine, who was born 12 March 1710, Susanna Maria (afterwards celebrated as Mrs. Gibber), and other children. Thomas Augustine was educated at Eton, where he does not seem to have distinguished himself otherwise than as a performer on the flute, and on leaving school was placed by his father in a lawyer's office. During this period of his life, the love of music which had characterised his Eton career speedily developed although his passion had to be concealed from his father. He privately took lessons on the violin from Michael Testing, and practised the spinet at night on an instrument he had secretly conveyed to his room, the strings of which he muffled with handkerchiefs. He also devoted himself to the study of harmony and composition, and, disguised in a borrowed livery, used to frequent the opera-house galleries to which servants had free admittance. His musical progress was so marked that he was soon able to lead a chamber band of amateurs, and it was when so engaged that young Arne was one day found by his astonished father. The discovery of his son's musical talents Was at first met with a considerable display of wrath on the part of Thomas Arne, but eventually he had the good sense to recognise that the boy was more fitted for a musician than a lawyer, and after some hesitation to allow him to cultivate the talents which he so decidedly displayed. Not content with cultivating his own abilities, Arne henceforward turned his attention to the dormant faculties of his sister and brother, to the former of whom he gave such instruction in singing as to lead to her appearance on the operatic stage in Lampe's opera 'Amelia 'in March 1732. Encouraged by the success she achieved, he wrote new music for Addison's opera 'Rosamond,' which was produced at the Lincoln's Inn Fields theatre, on 7 March 1733, with Mrs. Barbier, Miss Arne, Mrs. Jones, Miss Chambers, Leveridge, Corfe, and the composer's younger brother in the principal parts, and was played for ten nights successively. His next work was a version of Fielding's 'Tom Thumb,' altered into 'The Opera of Operas,' a musical burlesque, which was produced at the Haymarket, 31 May 1733, and was acted eleven times. In the same year he produced (19 Dec.) at the same theatre a masque, 'Dido and Æneas,' in which both his brother and sister sang. Early in the following year the Arne family were engaged at Drury Lane, Miss Arne and 'young Master Arne' as singers, and the composer in some capacity which is not recorded, though, from the fact of his haying benefits on 29 April and 3 June, he must have already had some recognised post. In April 1734 Susanna Arne married Theophilus Cibber [see Cibber, Mrs.], and in 1736 Arne wrote music for the play of 'Zara,' in which she for the first time appeared as an actress. In the same year Arne married the singer Gecilia Young [see Arne, Gecilia]. On 4 March 1738 Milton's 'Comus,' with additions and alterations by Dr. Dalton, was produced at Drury Lane, the principal parts being performed by Quin, Milward, Cibber jun., Mills, Beard, Mrs. Cibber, Mrs. Clive, and Mrs. Arne. For this performance Arne wrote his well-known and charming music, which still retains the freshness and delicacy of its melody. In this work Arne already shows himself a master of the peculiarly English style which is the great charm of his music; he entered thoroughly into the spirit of Milton's masque, his setting of the words of some of the songs showing a degree of poetical and musical insight which is surprising at the period at which he wrote. Considering the beauty of the music and the strength of the cast, it is surprising to find that 'Comus' was played only about eleven times, though it was subsequently frequently revived at both houses, and has kept the stage almost until the present day. Arne's next works were settings of two masques, Congreve's 'Judgment of Paris,' and Thomson and Mallet's 'Alfred.' Both of these were performed on Friday and Saturday, 1 and 2 Aug. 1740, on a stage erected in the gardens of the house of Frederick, Prince of Wales, at Cliveden, Bucks, at a fête given in commemoration of the accession of George I and in honour of the birth of the Princess Augusta. The programme also included 'several scenes out of Mr. Rich's pantomime entertainments' (Gent. Mag. 1740, p. 411). This performance is memorable in the annals of English music, for it was for 'Alfred' that Arne composed 'Rule Britannia,' perhaps the finest national song possessed by any nation, and for which alone, even if he had produced nothing else, Arne would deserve a prominent place amongst musicians of all countries. Shortly after this performance, 'The Judgment of Paris' was given at Drury Lane, though 'Alfred' was not produced in London until 30 March 1745, when it was performed at Drury Lane for Mrs. Arne's benefit. In about 1740 or 1741 Arne (who was then living at Craven Buildings, near Drury Lane) obtained a royal grant assuring to him the copyright of his compositions for four-teen years. After producing several minor pieces at Drury Lane — amongst which is the beautiful music to 'As You Like It' and 'Twelfth Night' — Arne and his wife, towards the end of 1742, went to Dublin, where they remained until the end of 1744, both husband and wife winning fresh laurels as musician and singer. On their return from Ireland, Mrs. Arne was re-engaged at Drury Lane, and Arne was appointed composer to the same theatre, a post there is reason to believe he had occupied before; somewhat later he was appointed leader of the band of the theatre. At this time Arne was living 'next door to the Crown' in Great Queen Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields, but he seems soon to have removed, first to Charles Street, and eventually to the house in the Piazza, Covent Garden, which he occupied until his death. In 1745 Mrs. Arne was engaged at Vauxhall Gardens, while Arne was also commissioned to write songs for the concerts held at the same place. For Vauxhall, Marylebone, and Ranelagh he for many years wrote an immense number of detached songs and duets, many of which, though now forgotten, are well worth revival. In 1746 he wrote songs for a performance of 'The Tempest' at Drury Lane, amongst which is the charming setting of 'Where the Bee sucks,' which, after 'Rule Britanria,' is probably now the best remembered of his compositions. Two years later, on the death of Thomson, Mallet determined to remodel 'Alfred;' in its altered form it was produced at Drury Lane in Feb. 1751, on which occasion three additional stanzas were added to 'Rule Britannia;' these extra verses were said to have been written by Bolingbroke a few days before his death (Davies, Memoirs of Garrick, London, 1808). About this time Mrs. Arne left off singing in public, her place being henceforth taken by the numerous pupils whom Arne brought before the public. As a teacher he enjoyed a great and deserved reputation, one secret of his success being the great importance he attached to the clear enunciation of the words in singing. His most distinguished pupil was Miss Brent, for whom he composed a number of bravura airs, which, being generally written for the display of her remarkable powers of execution, are of less value than the refined and delicate songs he wrote at an earlier period for his wife. For these occasional songs and airs he received twenty guineas for every collection of eight or nine compositions (Add. MS. 28959). On 12 March 1755, he produced his first oratorio, 'Abel;' but neither this nor a svibsequent work, 'Judith' (produced at the chapel of the Lock Hospital, Pimlico, on 29 Feb. 1764) achieved any success, mainly, it is said, owing to the inadequacy of the forces at his disposal for the performances. On 6 July 1759, the university of Oxford conferred upon Arne the degree of doctor of music. The relations of Arne with Garrick at this period seem to have become rather strained. Garrick was no musician, and Arne, whose talent was beginning to suffer from overproduction, had written one or two works for Drury Lane (then under Garrick's management) which had been decided failures. It is therefore not surprising to find that in 1760 Arne transferred his services to the rival house of Covent Garden, where, on 28 Nov. 1760, his 'Thomas and Sally' was played with Beard, Mattocks, and Miss Brent in the chief parts. Arne's next venture was a bold one, but, as the result proved, perfectly successful. Determined to give Miss Brent an exceptional opportunity for the display of her powers, he translated the Abbate Metastasio's 'Artaserse,' setting it to music in the florid and artificial style of the Italian opera of the day. The opera was produced at Covent Garden on 2 Feb. 1762, the parts of Mandane, Arbaces, Artabanes, Artaxerxes, Rimenes and Semira being respectively filled by Miss Brent, Tenducci, Beard, Peretti, Mattocks, and Miss Thomas. The work was immediately successful, and long kept the stage, yet Arne, when it was printed, only received from the publisher the trifling sum of sixty guineas for the copyright. 'Artaxerxes' was followed by several works of no great importance, the chief of which were 'Love in a Village,' a successful pasticcia produced in 1762; and a setting, to the original Italian words, of Metastasio's 'Olimpiade,' a work which was produced at the Haymarket in 1764, but was only performed twice. In 1765 Arne was for a short time a member of the Madrigal Society (Records of the Madrigal Soc). In 1769 Garrick, with whom Arne, though never on very good terms, seems to have always kept up some sort of intercourse, commissioned the composer to write music for the ode performed at the Shakespeare jubilee at Stratford-on-Avon. For this setting of Garrick's verses Arne received 63l., and in addition to this a performance of his oratorio 'Judith' at the parish church was somewhat incongruously included in the programme of the festivities in honour of Shakespeare. Arne now remained on tolerably good terms with the managers of both houses, and the record of the rest of his life consists of little more than a chronicle of the production of numerous light operas and incidental music written for different plays. During these years (from 1769 until 1778) he composed and wrote music for the following works: 'The Ladies' Frolic,' 'The Cooper,' 'May Day,' 'The Rose' (said to have been written by 'an Oxford student,' but generally attributed to Arne), 'The Fairy Prince,' 'The Contest of Beauty and Virtue,' 'Phœbe at Court,' 'The Trip to Portsmouth,' and Mason's tragedies of 'Elfrida' and 'Caractacus.' The latter work was published in 1775, with a preface and introduction in which Arne shows a curious insight into the relationship between dramatic poetry and music. He expresses opinions on the subject, the truth of which, though couched in the stilted language of the period, is only beginning to be recognised at the present day. The overture to the same work is a singular attempt at programme music, and the minute directions as to the constitution of the orchestra and manner of performance almost forestall the similar annotations to be found in the works of Hector Berlioz. During the latter years of Arne's life he achieved but few successes. He was fond of writing his own libretti, which were, unfortunately, anything but good, and the failure of his pupils at one opera-house—particularly if another pupil had been successful at the rival house—caused little bickerings which jarred upon his sensitive nature. In August 1775 he wrote to Garrick, complaining of the latter's neglect: 'These unkind prejudices the Doctor can no other wise account for than as arising from an irresistable Apathy,' a statement to which Garrick replied a few days later: 'How can you imagine that I have an in-esistable Apathy to you? I suppose you mean Antipathy, my dear Doctor, by the construction and general turn of your letter—be assur'd as my nature is very little inclined to Apathy, so it is as far from conceiving an Antipathy to you or any genius in this or any other country,' in spite of which polite assurance Garrick wrote in the same year: 'I have read your play and rode your horse, and do not approve of either;' endorsing the pithy note, 'Designed for Dr. Arne, who sold me a horse, a very dull one; and sent me a comic opera, ditto' (Gaemck's Correspondence, Forster Collection). These few glimpses of Arne's personal characteristics hardly carry out the statement of a contemporary that 'his cheerful and even temper made him endure a precarious pittance' (Dibdin, Musical Tour, letter lxv.); yet after his death it seems generally to have been considered that during his lifetime his genius was never sufficiently appreciated, and that as a musical hack, expected to supply music for the ephemeral plays produced at both Covent Garden and Drury Lane, he frittered away the talents which ought to have been devoted to better work. His death took place on 5 March 1778. According to the account of an eye-witness (Joseph Vernon, the singer) he died of a spasmodic complaint (Gent. Mag. vol. xlviii.) in the middle of a conversation on some musical matter, with his last breath trying to sing a passage the meaning of which he was too exhausted to explain. He was buried in St. Paul's, Covent Garden. The best portrait extant of Arne is an oil painting by Zoffany, now in the possession of Henry Littleton, Esq., but there is also an engraving of him after Dunkarton, and another (published 10 May 1782) after an original sketch by Bartolozzi.

A caricature of Rowlandson's, entitled 'A Musical Doctor and his Pupils,' is also probably meant for Arne. Manuscripts of his music are now rarely found, most of them having been destroyed when Covent Garden theatre was burnt in 1808, but the full autograph score of 'Judith' is preserved in the British Museum (Add. MSS. 11515-17).

[Grove's Dictionary of Music, i. 84; Burney's Life of Arne, in Rees's Cyclopædia, vol. ii., 1819, Genest, vols. iii. and iv.; Busby's Concert-room Anecdotes, 1825; Busby's History of Music, 1819, vol. ii.; Registers of Westminster Abbey; Victor's History of the London Theatres, 1761-1771; Parke's Musical Memoirs, vol. i., 1830; the Harmonicon for 1825; Notes and Queries (2nd series), iv. 415, v. 91, 316, 319; and the authorities quoted above.]

W. B. S.

Encyclopædia Britannica 11th edition (1911)

ARNE, THOMAS AUGUSTINE (1710–1778), English musical composer, was born in London on the 12th of March 1710, his father being an upholsterer. Intended for the legal profession, he was educated at Eton, and afterwards apprenticed to an attorney for three years. His natural inclination for music, however, proved irresistible, and his father, finding from his performance at an amateur musical party that he was already a skilful violinist, furnished him with the means of educating himself in his favourite art. On the 7th of March 1733 he produced his first work at Lincoln’s Inn Fields theatre, a setting of Addison’s Rosamond, the heroine’s part being performed by his sister, Susanna Maria, who afterwards became celebrated as Mrs Cibber. This proving a success was immediately followed by a burletta, entitled The Opera of Operas, based on Fielding’s Tragedy of Tragedies. The part of Tom Thumb was played by Arne’s young brother, and the opera was produced at the Haymarket theatre. On the 19th of December 1733 Arne produced at the same theatre the masque Dido and Aeneas, a subject of which the musical conception had been immortalized for Englishmen more than half a century earlier by Henry Purcell. Arne’s individuality of style first distinctly asserted itself in the music to Dr Dalton’s adaptation of Milton’s Comus, which was performed at Drury Lane in 1738, and speedily established his reputation. In 1740 he wrote the music for Thomson and Mallet’s Masque of Alfred, which is noteworthy as containing the most popular of all his airs—“Rule, Britannia!” In 1740 he also wrote his beautiful settings of the songs, “Under the greenwood tree,” “Blow, blow, thou winter wind” and “When daisies pied,” for a performance of Shakespeare’s As You Like It. Four years before this, in 1736, he had married Cecilia, the eldest daughter of Charles Young, organist of All Hallows Barking. She was considered the finest English singer of the day and was frequently engaged by Handel in the performance of his music. In 1742 Arne went with his wife to Dublin, where he remained two years and produced his oratorio Abel, containing the beautiful melody known as the Hymn of Eve, the operas Britannia, Eliza and Comus, and where he also gave a number of successful concerts. On his return to London he was engaged as leader of the band at Drury Lane theatre (1744), and as composer at Vauxhall (1745). In this latter year he composed his successful pastoral dialogue, Colin and Phoebe, and in 1746 the song, “Where the bee sucks.” In 1759 he received the degree of doctor of music from Oxford. In 1760 he transferred his services to Covent Garden theatre, where on the 28th of November he produced his Thomas and Sally. Here, too, on the 2nd of February 1762 he produced his Artaxerxes, an opera in the Italian style with recitative instead of spoken dialogue, the popularity of which is attested by the fact that it continued to be performed at intervals for upwards of eighty years. The libretto, by Arne himself, was a very poor translation of Metastasio’s Artaserse. In 1762 also was produced the ballad-opera Love in a Cottage. His oratorio Judith, of which the first performance was on the 27th of February 1761 at Drury Lane, was revived at the chapel of the Lock hospital, Pimlico, on the 29th of February 1764, in which year was also performed his setting of Metastasio’s Olimpiade in the original language at the King’s theatre in the Haymarket. At a later performance of Judith at Covent Garden theatre on the 26th of February 1773 Arne for the first time introduced female voices into oratorio choruses. In 1769 he wrote the musical parts for Garrick’s ode for the Shakespeare jubilee at Stratford-on-Avon, and in 1770 he gave a mutilated version of Purcell’s King Arthur. One of his last dramatic works was the music to Mason’s Caractacus, published in 1775. Though inferior to Purcell in intensity of feeling, Arne has not been surpassed as a composer of graceful and attractive melody. There is true genius in such airs as “Rule, Britannia!” and “Where the bee sucks,” which still retain their original freshness and popularity. As a writer of glees he does not take such high rank, though he deserves notice as the leader in the revival of that peculiarly English form of composition. He was author as well as composer of The Guardian outwitted, The Rose, The Contest of Beauty and Virtue, and Phoebe at Court. Dr Arne died on the 5th of March 1778, and was buried at St Paul’s, Covent Garden.

See also the article in Grove’s Dictionary (new ed.); and two interesting papers in the Musical Times, November and December 1901.