Samuel Richardson (1689–1761; fl. 1719–1761)

Samuel Richardson, author, printer, publisher, and stationer (1719–1761); in Fleet Street; in Salisbury Court; in White Lyon Court.

Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900)

RICHARDSON, SAMUEL (1689–1761), novelist, was born in 1689 at some place in Derbyshire never identified. His father was the descendant of a family ‘of middling note’ in Surrey, which had so multiplied that his share in the inheritance was small. He became a joiner and carpenter. He had also some knowledge of architecture, and was employed by the Duke of Monmouth and the first Earl of Shaftesbury. Their favour led to suspicions of his loyalty, and upon the failure of Monmouth's rebellion he gave up business in London and retired to the country. His wife was of a family ‘not ungenteel,’ and it would appear that in some way she was connected with persons able to be of use to her family.

Samuel, one of nine children, was intended for the church, but losses of money compelled his father to put him to trade instead of sending him to the university. He is said to have been for a time at Christ's Hospital (Nichols, Lit. Anecd. iv. 578). His name, however, does not appear in the school registers (information from Mr. Lempriere of Christ's Hospital), and, in any case, he never acquired more than a smattering of learned languages. His early recollections imply that he lived till the age of thirteen in the country. He says that he was ‘bashful and not forward,’ but he gave early proofs of his peculiar talent. He cared little for boyish games, but used to tell stories to amuse his playfellows, one of which was a history of a ‘fine young lady’ who preferred a virtuous ‘servant man’ to a ‘libertine lord.’ Before he was eleven he also wrote an admonitory letter to a sanctimonious widow of near fifty, proving by a collection of texts the wickedness of scandal. He became a favourite with young women, read to them while they were sewing, and was employed by three of them independently to compose love-letters.

In 1706 he was bound apprentice to John Wilde, a stationer, and served an exacting master faithfully. He managed to employ his brief leisure in reading and in carrying on a correspondence with ‘a gentleman of ample fortune,’ who, ‘had he lived, intended high things for me.’ These letters were burnt at his correspondent's desire, and it does not appear who the gentleman was. After serving his time, Richardson worked for some years as compositor and corrector of the press at a printing office, and in 1719 took up his freedom and started in business—first in Fleet Street, and soon afterwards in Salisbury Court, where he lived for the rest of his life. He is mentioned as of ‘Salisbury Court’ in 1724, when he was one of the printers ‘said to be high-flyers’ (Nichols, Lit. Anecd. iii. 311). He married Martha, the daughter of Allington Wilde of Aldersgate Street, another ‘high-flying’ printer (whom Mrs. Barbauld confuses with his master, John Wilde). In 1723 he printed the first six numbers of the ‘True Briton,’ a violent opposition paper, for the Duke of Wharton, and is conjectured to have written the last number himself (ib. iv. 580). He appears, however, to have been prudent enough to avoid libellous publications. He had some connection with Arthur Onslow [q. v.], who in 1728 became speaker, and through Onslow's interest he was entrusted with printing the ‘Journals’ of the House of Commons. He ultimately printed twenty-six volumes, and he mentions that a sum of 3,000l. was due to him at one time upon this account. He also, in 1736–7, printed the ‘Daily Journal,’ and in 1738 the ‘Daily Gazetteer.’ He had clearly not allowed his high-flying principles to interfere with his business. Some noblemen and authors formed in 1736 ‘a society for the encouragement of learning,’ and appointed him to be one of their printers. The society, which was intended to make authors independent of publishers, and was looking out vainly for a man of genius to start their business, soon collapsed (ib. ii. 90–5).

In 1739 two booksellers, Rivington and Osborne, proposed to Richardson that he should write a volume of familiar letters as patterns for illiterate country writers. He remembered, as he says, an anecdote which he had heard from a friend, and made the incidents a theme for the imaginary letters. In this way ‘Pamela’ was composed between 10 Nov. 1739 and 10 Jan. 1740. A similar story by Hughes in the ‘Spectator’ (No. 375) has been supposed to have given the hint. It was published by the end of 1740 (Correspondence, i. 53), and made at once a surprising success. It was soon translated into French and Dutch, and numerous English correspondents rivalled each other in eulogy. It was recommended from the pulpit; one writer placed it next to the bible, and ladies at Ranelagh held it up to their friends to show that they were not behindhand in the study. A spurious continuation, called ‘Pamela in High Life,’ was published, and Richardson was induced to add two volumes of his own of inferior merit. Warburton wrote to him (28 Dec. 1742) conveying praises from Pope and himself, and giving hints for future applications of the scheme. Richardson's correspondence shows that at a later time he felt little esteem for either of these great authorities. He was exceedingly provoked when Fielding ridiculed his performance in ‘Joseph Andrews,’ and ever afterwards spoke very bitterly of his rival, even to his rival's sisters. The contrast between the two men sufficiently explains Richardson's judgment without laying too much stress upon the merely personal resentment. Goldoni turned the novel into two plays—‘Pamela Nubile’ and ‘Pamela Maritata.’ It was also dramatised by James Dance, alias Love [q. v.], in 1742.

Richardson was beginning his next novel, ‘Clarissa Harlowe,’ in 1744 (ib. i. 97, 102). It was being read by Cibber in June 1745 (ib. ii. 127). The first four volumes, with a preface by Warburton, appeared in 1747, and the last four were published by the end of 1748 (ib. iv. 237). It eclipsed ‘Pamela,’ and very soon won for him a European reputation. In 1753 Richardson says that he had received from the famous Haller a translation into German, and that a Dutch translation by Stinstra was appearing (ib. vi. 244). There was a French translation, with omissions ‘to suit the delicacy of French taste,’ by the Abbé Prevost, and a fuller one afterwards by Le Tourneur. It brought Richardson a number of enthusiastic correspondents, especially Lady Bradshaigh, wife of Sir Roger Bradshaigh of Haigh, near Wigan. She began by anonymous letters of unbounded enthusiasm, though professing little acquaintance with literature. When he sent her his portrait, she changed her name to Dickenson, that she might not be supposed to correspond with an author. This was possibly the portrait which was afterwards in possession of ‘long’ Sir Thomas Robinson at Rokeby, who had a star and a blue riband painted upon it and christened it ‘Sir Robert Walpole,’ to fit it for aristocratic company (Southey's Life and Correspondence, iii. 347). Lady Bradshaigh, however, consented to become personally known to Richardson at the beginning of 1750, and afterwards saw him occasionally in the little circle where he received the worship of numerous, chiefly feminine, admirers. With them he elaborately discussed the moral and literary problems suggested by his works, and especially by his final performance, ‘Sir Charles Grandison.’ It was to be a pendant to the portrait of a good woman in ‘Clarissa,’ and he originally intended to call it ‘The Good Man.’ He was reading the manuscript and consulting various friends about it in 1751. It was published in 1753, and, though it has never held so high a position as ‘Clarissa,’ was received with equal enthusiasm at the time. His fame had attracted pirates, and the treachery of some of his workmen enabled Dublin booksellers to obtain and reprint an early, though not quite complete, copy. Richardson published a pamphlet, dated 14 Sept. 1755, complaining of his wrongs, and appears to have been greatly vexed by the injury. He was, however, prospering in his business. In 1754 he was chosen master of the Stationers' Company, a position, it is said, ‘not only honourable but lucrative’ (Correspondence, i. xlvi). In 1755 he pulled down his house at Salisbury Court, bought a row of eight houses, upon the site of which he erected a new printing office, and made a new dwelling-house of what had formerly been his warehouse. Everybody, he says, was better pleased with the new premises than his wife, which, as the new dwelling-house was less convenient than the old one, was not surprising. The trouble of the arrangement had, he said, diverted his mind from any further literary projects (ib. v. 63, 64). This house was demolished in 1896. In 1760 he bought half the patent of ‘law-printer to his majesty,’ and carried on the business in partnership with Miss Catherine Lintot. He had taken into partnership a nephew, who succeeded to the business. He had become nervous and hypochondriacal. He was rarely seen by his workmen in later years, and communicated with them by written notes, a circumstance perhaps explained by the deafness of his foreman. He died of apoplexy on 4 July 1761, and was buried by the side of his first wife in St. Bride's Church.

Richardson's first wife died on 25 Jan. 1730–1. All their children (five sons and a daughter) died in childhood—two boys in 1730. By his second wife, Elizabeth, sister of James Leake, a bookseller at Bath, he had a son, who died young, and five daughters. Four daughters survived him—Mary, married in 1757 to Philip Ditcher, a Bath surgeon; she died a widow in 1783; Martha, married in 1762 to Edward Bridgen; Anne, who died unmarried on 27 Dec. 1803; and Sarah, who married a surgeon named Crowther. The second Mrs. Richardson died on 3 Nov. 1773, aged 77, and was buried with her husband.

Richardson had a country house at North End, Hammersmith, now occupied by Sir Edward Burne-Jones. In this most of his novels were composed. He generally spent his Saturdays and Sundays there (ib. vi. 21). A picture of the house forms the frontispiece to the fourth volume of his ‘Correspondence,’ and a picture of the ‘grotto’ in the gardens, with Richardson reading the manuscript of ‘Sir Charles Grandison’ to his friends in 1751, forms the frontispiece to the second volume. In 1754 he moved to Parson's Green, Fulham (ib. iii. 99), where he generally had some friends to stay with him. The little circle of admirers never failed him, and he seems to have deserved their affection.

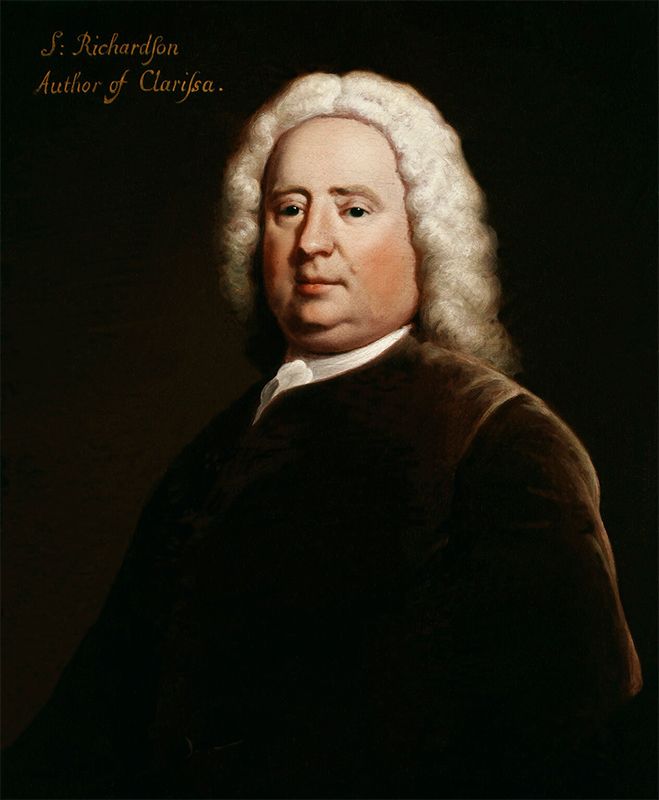

Richardson was a type of the virtuous apprentice—industrious, regular, and honest. He was a good master, and used to hide a half-crown among the types in the office so that the earliest riser might find it. Though cautious, and even fidgety, about business, he was exceedingly liberal in his dealings. He was generous to poor authors; he helped Lætitia Pilkington [q. v.] in her distresses; forgave a debt to William Webster [q. v.], who calls him ‘the most amiable man in the world’ (Nichols, Lit. Anecd. v. 165). Johnson, when under arrest for debt in 1756, applied to him with a confidence in his kindness justified by the result (see anecdotes in Birkbeck Hill's Boswell, i. 303 n.) Richardson appears to have made Johnson's acquaintance through the ‘Rambler’ (1750), to which he contributed No. 97. Johnson prefaced the paper with a note to the effect that the author was one who ‘taught the passions to move at the command of virtue,’ and, though not blind to Richardson's foibles, always extolled him as far superior to Fielding. Aaron Hill [q. v.] and Thomas Edwards [q. v.], who died in his house, and Young of the ‘Night Thoughts’ were among the authors with whom he exchanged compliments, and who found in him both a friend and a publisher. He appears to have been respected by his fellow-tradesmen, especially Cave, who exchanged verses with him (given in Nichols's Lit. Anecd. ii. 75) on occasion of a dinner of printers. Richardson, however, was unfit for the coarse festivities of the time, and was probably regarded as a milksop, fitter for the society of admiring ladies. He refers constantly to his nervous complaints, which grew upon him, and describes his own appearance minutely in a letter to Lady Bradshaigh (Correspondence, iv. 290). He was about 5 ft. 5 in. in height, plump, and fresh-coloured; he carried a cane to support him in ‘sudden tremors;’ stole quietly along, lifting ‘a grey eye too often overclouded by mistinesses from the head’ to observe all the ladies whom he passed, looking first humbly at their feet, and then taking a rapid but observing glance at their whole persons. A portrait, by Joseph Highmore [q. v.] (with a companion portrait of Mrs. Richardson), is in the Stationers' Hall. An engraving from this forms the frontispiece to the first volume of the ‘Correspondence.’ Two others by Highmore are in the National Portrait Gallery. A portrait, by Mason Chamberlin [q. v.], ‘in possession of the Earl of Onslow,’ was engraved by Scriven in 1811.

Richardson's vanity, stimulated by the little coterie in which he lived, was an appeal for tenderness as much as an excessive estimate of his own merits. He fully accepted the narrow moral standard of his surroundings, and his dislike of Fielding and Sterne shows his natural prejudices. His novels represented the didacticism of his time, and are edifying tracts developed into great romances. They owe their power partly to the extreme earnestness with which they are written. His correspondents discuss his persons as if they were real, and beg him to save Lovelace's soul (Corresp. iv. 195). Richardson takes the same tone. He wrote, as he tells us (ib. v. 258, vi. 116), ‘without a plan,’ and seems rather to watch the incidents than to create them. He spared no pains to give them reality, and applied to his friends to help him in details with which he was not familiar. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu could not help weeping over Clarissa ‘like a milkmaid,’ but declares that Richardson knew nothing of the manners of good society (Letters, 1 March and 20 Oct. 1752), and was no doubt a good judge upon that point. Chesterfield, who, however, recognises his truth to nature, and Horace Walpole make similar criticisms (Walpole, Correspondence, ed. Cunningham, iv. 305 n.) The minute realism of his stories convinced most readers of their truthfulness. But his influence was no doubt due chiefly to his sentimentalism. Lady Bradshaigh begs him in 1749 to tell her the meaning of this new word ‘sentimental,’ which has come into vogue for ‘everything that is clever and agreeable’ (Corresp. iv. 283). Richardson's works answer her inquiry, and, though polite circles were offended by his slovenly style and loose morality, the real pathos attracted the world at large. He was admired in Germany, whence Klopstock's first wife wrote him some charming letters, and the Moravians invited him to visit them. A Dutch minister declared that parts of ‘Clarissa,’ if found in the Bible, would be ‘pointed out as manifest proofs of divine inspiration’ (Corresp. v. 242). His success was most remarkable in France, where Diderot wrote of him with enthusiasm (see remarks in Morley's Diderot, ii. 44–9; cf. Texte, Rousseau et le Cosmopolitisme Littéraire au xviiie siècle, chap. v. 1895), and Rousseau made him a model for the ‘Nouvelle Héloïse.’ In his letter to D'Alembert, Rousseau says that there is in no language a romance equal to or approaching ‘Clarissa.’ Richardson, it is said (Nichols, Anecd. iv. 198), annotated his disciple's performance in a way which showed ‘disgust.’ In England, Richardson's tediousness was felt from the first. ‘You would hang yourself from impatience,’ as Johnson said to Boswell (6 April 1772), if you read him for the story. The impatience, in spite of warm eulogies by orthodox critics, has probably grown stronger. His last enthusiastic reader was Macaulay, who told Charles Greville (Queen Victoria, ii. 70) that he could almost restore ‘Clarissa’ if it were lost. The story of his success in infecting his friends in India with his enthusiasm is told in Thackeray's ‘Roundabout Papers’ (Nil nisi bonum), and confirmed in Sir G. Trevelyan's ‘Life.’ Probably Indian society was then rather at a loss for light literature.

The dates of publication of Richardson's three novels have been given above. The British Museum contains French translations of ‘Pamela,’ dated 1741 (first two volumes) and 1742; of ‘Clarissa Harlowe,’ 1785, and, by Jules Janin, 1846; of ‘Grandison,’ 1784; Italian translations of ‘Clarissa,’ 1783, and of ‘Grandison,’ 1784–9; and a Spanish translation of ‘Grandison,’ 1798. Abridgments of ‘Clarissa’ by E. S. Dallas and one by Mrs. Ward were published in 1868; and an abridgment of ‘Grandison’ by M. Howell in 1873. An edition of the novels by Mangin, in nineteen volumes, crown 8vo, appeared in 1811. ‘Clarissa’ and ‘Grandison’ are in the ‘British Novelists’ (1820), vols. i. to xv.; the three novels are in Ballantyne's ‘Novelists Library’ (1824), vols. vi. to viii.; and an edition of the three in twelve volumes, published by Sotheran, appeared in 1883. A ‘Collection of the Moral and Instructive Sentiments,’ &c., in the three volumes, was published in 1755. Richardson published editions of De Foe's ‘Tour through Great Britain’ in 1742 and later years with additions; and in 1740 edited Sir Thomas Roe's ‘Negotiations in his Embassy to the Ottoman Porte.’ His ‘Correspondence,’ selected from the ‘Original Manuscripts bequeathed to his family,’ was edited by Anna Letitia Barbauld in 1804 (London, 6 vols. 8vo).

[The chief authority for Richardson's life is the biographical account by Mrs. Barbauld prefixed to his Correspondence, 1804. Most of the letters, from which the correspondence is extracted, are now in the Forster Library at South Kensington. The collection includes many unpublished letters, copies of poems, &c., but does not contain all the letters used by Mrs. Barbauld. There is also a life in Nichols's Lit. Anecd. iv. 578–98, and many references in other volumes, see index. In ‘Notes and Queries,’ 5th ser. viii. 107, are extracts from a copy of ‘Clarissa,’ annotated by Richardson and Lady Bradshaigh; and in 4th ser. i. 885, iii. 375, some unpublished letters of Richardson.]

L. S.

Dictionary of National Biography, Errata (1904), p. 234

N.B.— f.e. stands for from end and l.l. for last line

| Page | Col. | Line | |

| 246 | ii | 13 f.e. | Richard, Samuel (1689-1761): for M. Howell read Mary Howitt |

Encyclopædia Britannica 11th edition (1911)

RICHARDSON, SAMUEL (1680–1761), English novelist, is a notable example of that “late-flowering” sometimes applied to Oliver Goldsmith. Born under William and Mary, the reign of the second George was well advanced before, at fifty years of age, he made his first serious literary effort—an effort which was not only a success, but the revelation of a new literary form. He was the son of a London joiner, who, for obscure reasons, probably connected with Monmouth's rebellion, had retired to an unidentified town in Derbyshire, where, in 1689, Samuel was born. At first intended for holy orders, and having little but the common learning of a private grammar school—for the tradition that upon the return of the family to the metropolis he went to Christ's Hospital cannot be sustained—he was eventually, as some compensation for a literary turn, apprenticed at seventeen to an Aldersgate printer named John Wilde. Here, like the typical “good apprentice” of his century, he prospered; became successively compositor, corrector of the press, and printer on his own account; married his master's daughter according to programme; set up newspapers and books; dabbled a little in literature by compiling indexes and “honest dedications,” and ultimately proceeded Printer of the Journals of the House of Commons, Master of the Stationers' Company, and Law-Printer to the King. Like all well-to-do citizens, he had his city-house of business and his “country box” in the suburbs; and, after a thoroughly respectable” life, died on the 4th of July 1761, being buried in St Bride's Church, Fleet Street, close to his shop (now demolished), No. 11 Salisbury Court.

To this uneventful and conventional career one would scarcely look for the birth and growth of a fresh departure in fiction. And yet, although Richardson's manifestation of his literary gift was deferred for half a century, there is no life to which the Horatian “qualis ab incepto” can be more appropriately applied. From his youth this moralist had moralized from his youth—nay, from his childhood—this letter-writer had written letters; from his youth this supreme delineatorr of the other sex had been the confidant and counsellor of women. In his boyhood he was secretary-general to all the love-sick girls of the neighbourhood; at eleven he addressed a hortatory epistle, stuffed with texts, to a scandal-loving widow; and whenever it was possible to correspond with any one he was as “corresponding” as even Horace Walpole could have desired. At last, when he was known to the world only as a steady business man, who was also a “dab at an index” and an invaluable compiler of the “puff prefatory," it occurred to Mr Rivington of St Paul's Churchyard and Mr Osborn of Paternoster Row, two book selling friends who were aware of his epistolary gifts, to suggest that he should prepare a little model letter-writer for such “country readers” as “were unable to indite for themselves.” Would it be any harm, he suggested in answer, if he should also “instruct them how they should think and act in common cases”? His friends were all the more anxious that he should set to work. And thus originated his first novel of Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded.

But not forthwith, as is sometimes supposed. Proceeding with the compilation of his model letter-writer, and seeking, in his own words, “to instruct handsome girls, who were obliged to go out on service ... how to avoid the snares that might be laid against their virtue”—a danger which appears to have always abnormally preoccupied him—he came to recollect a story he had heard twenty years earlier, and had often proposed to other persons for fictitious treatment. It occurred to him that it would make a book of itself, and might moreover be told wholly in the fashion most congenial to himself, namely, by letters. Thereupon, with some domestic encouragement, he completed it in a couple of months, between the 10th of November 1739 and the 10th of January 1740. In November 1740 it was issued by Messrs Rivington & Osborn, who, a few weeks afterwards (January 1741), also published the model letter writer under the title of Letters written to and for Particular Friends, on the most Important Occasions. Both books were anonymous. The letter-writer was noticed in the Gentleman's Magazine for January, which also contains a brief announcement as to Pamela, already rapidly making its way without waiting for the reviewers. A second edition, it was stated, was expected; and such was its popularity, that not to have read it was judged “as great a sign of want of curiosity as not to have seen the French and Italian dancers ”—i.e. Mme Chateauneuf and the Fausans, who were then delighting the town. In February a second edition duly appeared, followed by a third in March and a fourth in May. At public gardens ladies held up the book to show they had got it; Dr Benjamin Slocock of Southwark openly commended it from the pulpit; Pope praised it; and at Slough, when the heroine triumphed, the enraptured villagers rang the church bells for joy. The other volume of “familiar letters” consequently fell into the background in the estimation of its author, who, though it went into several editions during his lifetime, never acknowledged it. Yet it scarcely deserves to be wholly neglected, as it contains many useful details and much shrewd criticism of lower middle-class life.

For the exceptional success of Pamela there was the obvious novelty. People were tired of the old “mouthy” about impossible people doing impossible things.

Here was a real-life story, which might happen to any one—a story which aroused curiosity and arrested attention—which was not exclusively about “high life,” and which had, in addition, a moral purpose, since it was avowedly “published in order to cultivate the principles of virtue and religion in the minds of the youth of both sexes.” Whether it had exactly this effect, or owed its good fortune chiefly to this proclamation, may be doubted. The heroine in humble life who resists the licentious advances of her master until he is forced to marry her, does not entirely convince us that her watchful prudence and keen eye for the main chance have not, in the long run, quite as much to do with her successful defence as her boasted innocence and purity. Nor is the book without passages which more than smack of an unpleasant prurience. Nevertheless, in its extraordinary gift of minute analysis; in its intimate knowledge of feminine character; in the cumulative power of its shufliing, loose-shod style, and, above all, in the unquestionable earnestness and sincerity of the writer, Pamela had qualities which—particularly in a dead season of letters—sufficiently account for its favourable reception by the contemporary public.

Such a popularity, of course, was not without its drawbacks. That it would lead to Anti-Pamelas, censures of Pamela and all the spawn of pamphlets which spring round the track of a sudden success, was to be anticipated. One of the results to which its rather sickly morality gave rise was the Joseph Andrews (1742) of Fielding (q.v.). But there are two other works prompted by Pamela which need brief notice here. One is the Apology for the Life of Mrs Shamela Andrews, a clever and very gross piece of raillery which appeared in April 1741, and by which Fielding is supposed to have preluded to Joseph Andrews. Fielding's own works contain no reference to Shamela. But Richardson in his Correspondence, both printed and unprinted, roundly attributes it to the writer who was to be his rival; and it is also assigned to Fielding by other contemporaries (Hist. MSS. Comn., Rept. 12, App. Pt. IX. p. 204). All that can be said is, that F ielding's authorship cannot be proved. If it could, it would go far to justify the after animosity of Richardson to Fielding—much farther, indeed, than what Richardson described as the “lewd and ungenerous engraftment” of Joseph Andrews. The second noteworthy result of Pamela was Pamela's Conduct in High Life (September 1741), a spurious sequel by John Kelly of the Universal Spectator. Richardson tried to prevent its appearance, and, having failed, set about two volumes of his own, which followed in December, and professed to depict his heroine “in her exalted condition.” But the public interest in Pamela had practically ceased with her marriage, and the author's continuation, like other continuations—particularly continuations prompted by extraneous circumstances—attracted no permanent attention.

About 1744 we begin to hear something of the progress of Richardson's second and greatest novel, Clarissa; or, the History of a Young Lady, usually miscalled Clarissa Harlowe. The first edition was in seven volumes, two of which came out in November 1747, two more in April 1748 and the last three in December. Upon the title-page of this, of which the mission was as edifying as that of Pamela, its object was defined as showing the distresses that may attend the misconduct both of parents and children in relation to marriage. Virtue, in Clarissa, is not “rewarded,” but hunted down and outraged. The heroine, no longer an opportunist servant-girl, is a most pure, refined and beautiful young woman, invested with every attribute to attract and charm, while her pursuer, Lovelace, the libertine hero of the book—a personage of singular dash and vivacity, in spite of his' worthlessness—is drawn with extraordinary tenacity of power. The wronged Clarissa eventually dies of grief, and her cold-blooded betrayer, whom strict justice would have hanged, is considerately killed in a duel by her soldier cousin. Of the genius of the story there can be no doubt. Nor is theref any doubt as to the ability shown in the delineation of the two chief characters, to whom the rest are merely subordinate. The chief drawbacks of Clarissa are its merciless prolixity (seven volumes, which only cover eleven months); the fact that (like Pamela) it is told by letters; and a certain haunting and uneasy feeling that many of the heroine's obstacles are only molehills which should have been readily surmounted. As to its success, accentuated as this was by its piecemeal method of publication, there has never been any question. Clarissa's sorrows set all England sobbing, and her fame and her fate spread rapidly to the Continent.

Between Clarissa and Richardson's next work appeared the Tom Jones of Fielding—a rival by no means welcome to the elder writer, although a rival who generously (and perhaps penitently) acknowledged Clarissa's rare merits.

“Pectus inaniter angit

Irritat, mulcet, falsis terroribus implet

Ut Magus,"

Fielding had written in the Jacobite's Journal. But even this could not console Richardsonfor the popularity of the “spurious brat” whom Fielding had made his hero, and his next effort was the depicting of a genuine fine gentleman—a task to which he was incited by a chorus of feminine worshippers. In the History of Sir Charles Grandison, “by the Editor of Pamela and Clarissa” (for he still preserved the fiction of anonymity), he essayed to draw a perfect model of manly character and conduct. In the pattern presented there is, however, too much buckram, too much ceremonial—in plain words, too much priggishness—to make him the desired exemplar of propriety in excelsis. Yet he is not entirely a failure, still less is he to be regarded as no more than “the condescending suit of clothes” by which Hazlitt unfairly defines Miss Burney’s Lord Orville. When Richardson delineated Sir Charles Grandson he was at his best, and his experiences and opportunities for inventing such a character were infinitely greater than they had ever been before. And he lost nothing of his gift for portraying the other sex. Harriet Byron, Clementina della Porretta and even Charlotte Grandison, are no whit behind Clarissa and her friend Miss Howe. Sir Charles Grandison, in fine, is a far better book than Pamela, although M. Taine regarded the hero as only fit to be stuffed and put in a museum.

Grandison was published in 1753, and by this time Richardson was sixty-four. Although the book was welcomed as warmly as its predecessors, he wrote no other novel, contenting himself instead with indexing his works, and compiling an anthology of the “maxims,” “cautions” and “instructive sentiments” they contained. To these things, as a professed moralist, he had always attached the greatest importance. He continued to correspond relentlessly with a large circle of worshippers, mostly women, whose counsels and fertilizing sympathy had not a little contributed to the success of his last two books. He was a nervous, highly strung little man, intensely preoccupied with his health and his feelings, hungry for praise when he had once tasted it, and afterwards unable to exist without it; but apart from these things, well meaning, benevolent, honest, industrious and religious. Seven vast folio volumes of his correspondence with his lady friends, and with a few men of the Young and Aaron Hill type, are preserved in the Forster Library at South Kensington. Parts of it only have been printed. There are several good portraits of him by Joseph Highmore, two of which are in the National Portrait Gallery.

Richardson is sometimes styled the “Father of the English Novel,” a title which has also been claimed for Defoe. It would be more accurate to call him the father of the novel of sentimental analysis. As Sir Walter Scott has said, no one before had dived so deeply into the human heart. No one, moreover, had brought to the study of feminine character so much prolonged research, so much patience of observation, so much interested and indulgent apprehension, as this twittering little printer of Salisbury Court. That he did not more materially control the course of fiction in his own country was probably owing to the new direction which was given to that fiction by Fielding and Smollett, whose method, roughly speaking, was synthetic rather than analytic. Still, his influence is to be traced in Sterne and Henry Mackenzie, as well as in Miss Burney and Miss Austen, both of whom, it may be noted, at first adopted the epistolary form. But it was in France, where the sentimental soil was ready for the dressing, that the analytic process was most warmly welcomed. Extravagantly eulogized by the great critic, Diderot, modified with splendid variation by Rousseau, copied (unwillingly) by Voltaire, the vogue of Richardson was so great as to tempt some modern French critics to seek his original in the Marianne of a contemporary analyst, Marivaux. As a matter of fact, though, there is some unconscious consonance of manner, there is nothing whatever to show that the little-lettered author of Pamela, who was also ignorant of French, had the slightest knowledge of Marivaux or Marianne. In Germany Richardson was even more popular than in France. Gellert, the fabulist, translated him; Wieland, Lessing, Hermes, all imitated him, and Coleridge detects him even in the Robbers of Schiller. What was stranger still, he returned to England again under another form. Having given a fillip to the French comédie larmoyante, that comedy crossed the channel as the sentimental comedy of Cumberland and Kelly, which, after a brief career of prosperity, received its death-blow at the hands of Goldsmith and Sheridan.

A selection from Richardson’s Correspondence was published by Mrs A. L. Barbauld in 1804, in six volumes, with a valuable Memoir. Recent lives are biy Miss Clara L. Thomson, 1900, and by Austin Dobson (“Men of Letters”), 1902. A convenient reprint of the novels, with copies of the old illustrations bv Stothard, Edward Burney and the rest, and an introduction by Mrs E. M. M. McKenna, was issued in 1901 in 20 volumes. (A. D.)

A Dictionary of the Printers and Booksellers who were at work in England, Scotland and Ireland from 1726 to 1775, by Henry Plomer et al. (1932)

RICHARDSON (SAMUEL), printer, publisher, and author, in London, (1) Fleet Street; (2) Salisbury Court; (3) White Lyon Court. 1719–61. Born in 1689 in Derbyshire, to which county his father had fled when the Duke of Monmouth was executed, young Samuel's early education was only such as was to be had at a dame's school. Leigh Hunt has left it on record that Richardson was later on a scholar at Christ's Hospital, but his statement is erroneous. [A.L. Reade in N. & Q. 10 S. xii. 301–3, 343–4.] Richardson appears to have been a strange lad, averse to active sport, and very much of a prig, probably due to his being thrown largely into the society of servants. It is said of him that while still a child he wrote a silly letter to a widow of about sixty, full of those virtuous sentiments that he afterwards embodied in the Familiar Letters and in his novels. The women servants gathered round him to listen to the sentimental semi-moral tales that, even as a boy, came easy to him. From this stage he passed to writing love-letters for his female friends. He was at length sent up to London and apprenticed to John Wilde, a printer in Aldersgate Street, in 1706. During the seven years of his apprenticeship he worked hard and had little leisure; but such as he had he devoted to reading and in corresponding with a wealthy gentleman, whose name is unknown, but who promised to help the young printer to advancement. This would-be benefactor died without carrrying out his promises, and the correspondence between them was burnt. Richardson is careful to tell us that whilst he was thus employed, in order not to waste his master's goods he used to buy his own candles. After his apprenticeship was ended Samuel Richardson continued to work with Wilde for another six years as journeymand and corrector of the business for himself in Fleet Street, and shortly afterwards married Martha Wilde, the daughter of his late master. Amongst the work put into his hands at this time was the printing of the True Briton, a newspaper that was making itself notorious. His name did not appear in the imprint of the first six numbers; after which he severed his connexion with it. Edmund Curll also stated in evidence before a Committee of the House of Commons, that he believed that Richardson was the printer of Mist's Journal of August 24th, 1728, which aroused the King's anger. [State Papers Dom., Geo. II, Bundle 8/33.] About this time he made the acquaintance of Charles Rivington, the founder of the great publishing house in Paternoster Row, and this ripened into a close friendship which continued until Rivington's death in 1742. It was at the instigation of Charles Rivington and John Osborne, another publisher in the "Row", that Richardson wrote the series of Familiar Letters that were published by them in 1740. The idea as set out in the title-page was not only to show the styles and forms to be observed in writing such letters, "but how to think and act justly and prudently in the common concerns of human life." This was the germ of Richardson's novels: Pamela, 1740; Clarissa, 1748; Sir Charles Grandison, 1753. The popularity of these works was enormous. They were even quoted from the pulpit, and while Henry Fielding ridiculed them, he nevertheless derived from Richardson more than the mere form of his parodies. These works Richardson printed at this own press; but in 1753 he was involved in a lawsuit with the printers of Dublin over a barefaced piracy of Sir Charles Grandison. The story is familiar, and need not be repeated here. Richardson lost his first wife in 1731, and soon afterwards married Elizabeth Leake, daughter of John Leake, London printer [N. & Q. 12 Ser. xi.224]. In 1742 his friend Charles Rivington died, and Richardson being nominated an executor of the will, took upon himself the guardianship of his late friend's two sons, John and James. For many years he was the printer of the Journals of the House of Commons, and in other ways his business had increased so largely that he found it necessary to build a new and larger printing-house in White Lyon Court in 1755. He soon afterwards entered into partnership with Catherine Lintot, the daughter of Henry Lintot, who held a moiety of the Patent for printing lawbooks. Samuel Richardson died in 1761. Although two sons had been born to him, both had died in infancy, and the business passed to his nephew. William Richardson. He was Master of the Stationers' Company in 1754. [Nichols, IV. 578–95; Knight, Shadows of the Old Booksellers; Austin Dobson, Samuel Richardson, 1902.]