Chiswick House

Pat Rogers, University of South Florida

August 2023

Often loosely styled a villa, this was a country retreat about six miles west of central London, at a time when Chiswick was not yet a suburb, but rather an outlying village. It joined numerous mansions of varying dimensions bordering on the Thames upstream from Richmond. Collectively they drew some extravagant praise from Daniel Defoe in 1724: “The river sides are … so full of beautiful buildings, charming gardens, and rich habitations of men of quality, that nothing in the world can imitate it.”

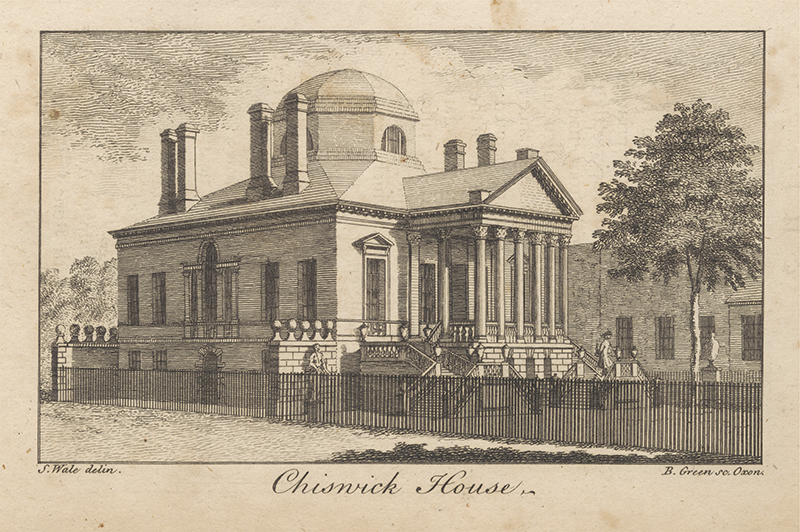

Shortly after these words were written, the owner and designer, Lord Burlington (1694–1753), began work on his new property, whose main structure was completed in 1728. He had inherited a Jacobean house on the site when succeeding to the earldom in 1703, and began to devote attention to the gardens around 1716. In the intervening years he had concentrated chiefly on his grand mansion off Piccadilly, Burlington House, where he had worked in collaboration with two major architects born in Scotland, the eclectic James Gibbs (1682–1754) and the securely Palladian Colen Campbell (1676–1729). Both men had some share in what went on at Chiswick, but the Earl had developed his own style after years of study of Italian models, first glimpsed on a Grand Tour in 1714–15 and a repeat visit in 1719. The principal source for his designs were the houses by Andrea Palladio (1508–1580) around Vicenza, such as the Villa Rotonda, which were also accessible to him in the editions of Palladio’s I Quattro Libro dell’ Achitectura that he collected. Equally important were drawings by Inigo Jones(1573–1652) and John Webb (1611–1672) that he acquired from William Talman (1650–1719) and from the house of Elihu Yale (1649–1721) in Queen Square.

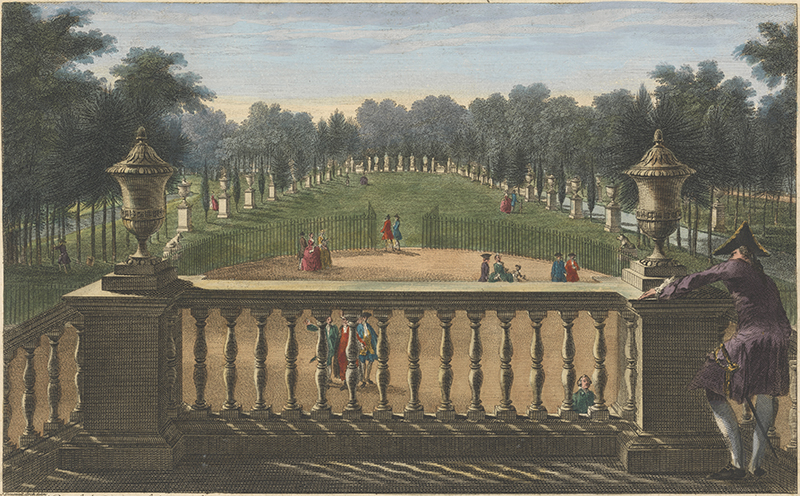

Work on the gardens continued after the main house was finished. They contained a large number of diverse ornamental features, including temples, statues, obelisks, follies, a canal, bridges, a cascade, archways, an orangery, groves, a conservatory, lawns, and terraces. The principal hand here was that of William Kent (1685–1748), house artist to Burlington, and his most devoted protégé. Some part early on was played by another notable figure in landscape garden design, Charles Bridgeman (c.1690–1738), while the Earl’s friend Alexander Pope was at hand as an amateur consultant. As Morris Brownell has observed, “Pope was a constant visitor to Chiswick, an admirer of the gardens, and intimately acquainted with improvements there.” He assured Burlington in 1732 that “Chiswick has been to me the finest thing this glorious Sun has shin'd upon.” In the Epistle to Burlington (1731), it is the sections on landscape gardening that are most prominent, and so the Earl’s patronage of leading designers at Chiswick is called up more insistently than his contributions to architecture in places like Burlington House (practically gardenless, as the northern portion of the estate had already been developed, and there was no way to expand in crowded Piccadilly).

Over the course of time, most of the Earl’s favourite furniture, pictures, and books were moved to Chiswick. He continued to use Burlington House on formal occasions, as well as passing summers at his country estate, Londesborough in East Yorkshire. However, it was Chiswick on which he tinkered most devotedly, at least until around 1740, when debts led to some retrenchment of his activities. After his own death in 1753 and that of his daughter Charlotte twelve months later, the property passed to Charlotte’s husband, who became the fourth Duke of Devonshire. Chiswick thus came into the possession of the Cavendish family for the better part of two centuries, and many of the contents were moved to Chatsworth. The Elizabethan house was demolished, and two new wings added. In the Victorian era, the villa was let to a number of tenants, including on one occasion the Prince of Wales. From 1892 to 1929 it was reduced to operating as a lunatic asylum. It was purchased by the Middlesex County Council in 1929, but remained in a “mutilated“ condition until it was restored by the Ministry of Works in the 1950s (John Harris). The gardens have also been rescued from previous neglect. Today the house and gardens are under the management of a trust formed jointly by Engllsh Heritage and the Borough of Hounslow, and they are open to the public.

All the essentials are covered by John Harris, The Palladian Revival: Lord Burlington, his Villa and Garden at Chiswick (Yale UP, 1994). For Pope’s involvement, see Morris R. Brownell, Alexander Pope and the Arts of Georgian England (Oxford, 1978).

A View of the Orangerie in Lord Burlington's Garden at Chiswick, by an unknown artist, n.d. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1995.13.167. Public Domain. |

Chiswick House, undated, print made by Benjamin Green, ca. 1736–ca. 1800. Yale Center for British Art; Yale University Art Gallery Collection, B1998.14.27. Public Domain. |

Chiswick House in Middlesex, the Seat of Duke of Devonshire, 1783, by William Watts (1752–1851). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.18675. Public Domain. |