The Grub-Street Journal

Pat Rogers, University of South Florida

February 2024

Grub Street, renown’d in old and modern times,

The venerable seat of prose and rhymes.The Grub-street Journal, 28 October 1731

The Journal ran for eight full years (1730–37) that followed the two earliest versions of The Dunciad. It was the organ by which the friends and allies of Alexander Pope kept up the assault on “Grub Street,” here interpreted as the home of mercenary compilers, plagiarists and other low-grade authors. Its pages can in fact be read as a kind of Dunciad in miniature. Functioning in part as a standard paper resembling outlets such as the Post Boy or Mist’s Weekly Journal in providing news and comment on issues of the day, it marked itself off by its satirical tone, its regular citation of passages from other newspapers for ridicule, and its principal emphasis on literature, or at least literary politics, rather than party politics. Although the run of the Grub Street Journal coincided with the most active period in the history of the Patriot Opposition to Robert Walpole, the editors ostentatiously declined to enter into matters of state. None the less, it is clear where the paper stood on many aspects of current affairs from its frequent broadsides against writers connected with, or supported by the Walpole administration, such as the courtier Lord Hervey, the poet laureate Colley Cibber, the “Thresher Poet” Stephen Duck, and the scholar Richard Bentley, all loyal adherents of the Hanoverian regime. The imputations are often indirect, as where the editors launch an attack in their early numbers on the notorious rapist, Colonel Francis Charteris, where the “sardonic contempt” of the treatment, as James T. Hillhouse calls it, is directed at the readiness of Walpole—known as the “Screen”—to cover up the misdemeanours of his cronies.

Origins

The first issue appeared on 8 January 1730, occupying a sheet and a half (six pages), at a price of twopence. On its opening page, the editors reveal their intention to present the history of the Society of Grub Street, as a potent rival to the annals of the Académie Française and the Royal Society of London. This salvo was launched in the midst of a fierce paper war involving writers who had been targets of Peri Bathous (1727) and The Dunciad. They were now leagued in opposition to Pope’s faithful advocates, who included members of the so-called Scriblerian group of satirists. Among the former group were miscellaneous authors and booksellers including William Bond, Eustace Budgell, Matthew Concanen, Thomas Cooke, Edmund Curll, John Dennis, John Henley, Nathanile Mist, Bezaleel Morris, John Oldmixon, Jonathan Smedley, James Moore Smythe, Lewis Theobald, and William Wilkins, all of whom reacted in some way to their unwanted presence in the poem. The allies of Pope included Richard Savage and James Miller.

The last issue, no. 418, came out on 29 December 1737, at a time when Pope himself had spent an undue amount of energy on his aggressive Imitations of Horace, and on the troublesome saga acted out in the publication of his correspondence, which had involved him in onerous legal battles with Curll. By the end of its run, the Journal was showing signs of exhaustion, and its two last numbers contained lengthy reprints of a pièce justicative that had appeared in an earlier selection of items published in book form. The paper was immediately followed by a sequel, The Literary Courier of Grub-Street, with a slightly modified programme. But as often, the rebranding did not work, and the new organ expired after six months.

The Journal kept up the pretence that it emerged from a tavern named the Flying Horse situated on the east side of Grub Street—a real establishment with this name was recorded from the middle of the seventeenth century. This title obviously suggests a kind of depraved Pegasus, winging its way over London to carry news and swooping on evil monsters from above. The real distributor was the experienced trade publisher James Roberts in Warwick Lane. The printer for most of the run was John Huggonson in Bartholomew Lane, behind the Royal Exchange, even though it is occasionally attributed to the pseudonymous “A. Moore.” The key member of the production team among the proprietors came to be Lawton Gilliver, a young bookseller operating in Fleet Street near Temple Bar, an area then thronged by members of the trade. He had been taken up by Pope a short time earlier. In the fifteenth issue of the Journal, “Capt. L. Gulliver” was elected bookseller to the imaginary Grubean Society who were supposedly behind the publication. How close Gilliver’s relations with the Scriblerian group were at this juncture is shown by the presence of advertisements in the paper for a highly contentious poem by Jonathan Swift entitled A Libel on Dr. D—ny and a Certain Great Lord, said to be “printed for Captain Gulliver near the Temple.” This formula was retained in the colophon to many issues of the Journal.

Editors

It is the general belief that Pope did not actively share in the editorial content of the paper. He might as well have done, because the writers invariably take his side and boost the value of his work in contrast to the pitiful performance of the hacks derided as the Grubean Society. Naturally, his many enemies claimed that he operated as the éminence grise. As remarked, a similar rollcall of villains to those of The Dunciad make their entrance. Some of his short epigrams might have appeared in the Journal, but there is no clear evidence to this effect. It is also impossible to trace with certainty any items in the paper that may have come from the hand of Pope’s Scriblerian colleague, Dr John Arbuthnot, although there are signs that he may have had some involvement. Four excerpts from the first year’s issues turned up briefly in appendix to The Dunciad during Pope’s lifetime. Two of these relate to the worm doctor, John Moore, and the dunce James Moore Smythe. They make little sense outside the context of a quarrel between Arbuthnot and Moore Smythe, reported exclusively in the columns of the Journal during the summer of 1730. By far the most natural explanation is that Arbuthnot fed this material to the editors. The first of the excerpts to be preserved in The Dunciad appendix (and, uniquely, retained in later editions of the poem) was “Of the Poet Laureate,” directed against Stephen Duck, while the last concerns practices of the Hottentots, now called the Khoikhoi people. Both show possible signs of Arbuthnot’s participation.

All along, the real heartbeat of the Journal was supplied by its principal editor, Richard Russel (1685–1746), an Oxford graduate, theological historian and nonjuring cleric who had been ejected from his living in Sussex after the Hanoverian accession. After an unsuccessful attempt at farming, he embarked on miscellaneous writing, and got to know some individuals with open or barely concealed Jacobite sympathies, among them Thomas Hearne and Richard Rawlinson. He seems to have carried out most of the day-to-day writing of the paper, as well as serving as one of the proprietors. According to his frequent butt, John Henley, he was an impoverished “runt with the name R---l” and “a mouse-eaten shred of an author.” He is said to have lived around College Street and supplemented his income by keeping a boarding house for the sons of nonjurors who attended nearby Westminster School.

At the beginning, Russel had the assistance of John Martyn FRS (1699–1768), who had started out as a counting house clerk for his father’s business off Cheapside, but emerged as a distinguished botanist after studying the works of Jean de Tournefort and achieving practical experience in the world of science. He also started one of the earliest botanical societies, which met at a coffee house in Watling Street. However, Martyn would abandon his editorial ship when he was elected to the chair of botany at Cambridge in 1733. He soon became disaffected with the university, and spent hardly any time there, even though he did not resign the post until 1762. In that year he was succeeded by his son Thomas (1735–1825), a clergyman who held on to this chair with other emoluments for sixty-three years, though as ODNB informs us, “he only lectured until 1796, botany not being a very popular subject.” Neither Russel or John Martyn ever repeated their successful venture into literary and political satire.

Initially each editor used the pseudonym of Bavius (the lead writer) and Maevius, poetasters mentioned in Virgil’s third Eclogue. Once more, Pope was ahead of his allies, as he had instanced one or both of these men in his poems, and actually found a small place for them in The Dunciad. In the third book, Bavius dips the fledging souls of reincarnated authors in the waters of Lethe to render them invulnerable, exactly as Thetis, the mother of Achilles, had tried to make her son proof against all threats. The characters of Bavius and Maevius by Russel especially are used to make sly commentaries on the follies of pamphlets and journalism that were emerging from the expanding print word of the capital.

Principal Targets

Early on, the Journal suggested a radical solution to the perennially difficult task of finding a suitable laureate:

The place of Poet Laureate becoming vacant by the death of the late Reverend Mr. Eusden, and several Candidates of equal merit pretending to the same, it is credibly reported, it will be put into Commission. The following persons are named for Commissioners, Stephen Duck, Labourer, Colly Cibber and James Moore, Esqs; L. Theobald, Attorney at Law, and John Dennis, Gentleman. We hope our gentle Readers will not be surprised at the mention of a dead person in this Commission; it being the opinion of many of our Members, that the Ode printed in Monday's Post Boy, must have been written either by him or the Rev. Mr. Eusden, likewise deceased: certain it is, that no man alive, could write such an one.

(5 November 1730)

Part of the joke is that none of the proposed candidates was actually dead. “Equal merit” provides a delicious touch. Among the paper’s targets, the most frequent victims of a sustained campaign were Cibber (1671–1757), Bentley (1662–1742), Theobald (1688–1744), Henley (1692–1756), and Curll (1683–1747), who were all by now grizzled veterans of combat in the London literary world. There are some amusing thrusts on the subject of the Poet Laureate’s skills as a tragic actor. For example, “In Bosworth-field he appears no more like King Richard, than King Richard was like Falstaff: he foams, struts, and bellows with the voice and cadence of a watch-man, rather than a hero and prince” (31 October 1734). The point strikes home more sharply because Cibber’s heavily cut Richard III (first performed 1700) was one of his greatest successes, when he wowed audiences with his portrayal of the King embellished with what William Hazlitt called gestures designed “to make the character as odious and disgusting as possible.” In 1730 he was still a leading figure in the London theatrical scene as actor-manager at Drury Lane. Naturally, it was the formal New Year and birthday odes required of a laureate that received the closest attention from the Journal, as they illustrated Cibber’s dependence on court patronage to establish any kind of poetic standing.

Bentley and Theobald inherited the scorn that the Scriblerians felt for over-attentive and unduly inventive verbal scholarship, both of which they managed to find in Bentley’s textual work and Theobald’s studies of Shakespeare. Even before Bentley’s “corrected” version of Paradise Lost came out in 1732, the Journal had offered some proleptic hints of the absurd emendations of the Miltonic text that they expected to find, and they were not disappointed by what emerged. The general complaint was the arrogance Bentley had shown: “For a person, who, tho' allowed to be a very learned Critic, was never imagined to be a Poet, to pour out in extemporary effusions, crude and indigested criticisms, upon the compleatest Poem in the English language; to pretend to alter and correct it in every page; to strike out great numbers of verses; and to put in many of his own; this justly raises the wonder, scorn, and indignation of all that hear it” (6 April 1732). The treatment of Theobald goes back to the harsh criticisms he had made of Pope’s editorial work in his book Shakespeare Restored (1726) and his edition of the playwright in 1733. Theobald was a harder target as there could be no doubt he had shown himself a better equipped commentator on Shakespeare and his age than Pope could claim to be. Nevertheless, the Journal found and pointed out a number of small errors and oddities in his notes, such as Theobald’s misleading use of a Greek votive tablet. All round, this was the weakest supplement to The Dunciad that the paper produced.

By contrast, Henley and Curll left some juicy fruit that the editors were able to pluck from low hanging branches. In particular Henley volunteered for the satirists’ lash by his eccentric actions, his relentless self-publicity and his outlandish ideas: “During the whole period of the Journal’s existence, and long after, he was continually and brazenly in the public eye” (James T. Hillhouse). This exposure was mainly the result of his unorthodox ministry at the ”Oratory” in Clare Market, located off Vere Street in an unfashionable quarter of the town lying between Lincoln’s In Fields and Drury Lane. The building stood out by reason of its unusual architecture, with the entrance through a paybox rather than a vestry or porch, and a row of spikes instead of a communion rail. The proceedings became decidedly strange over time, with a gradual abandonment of the traditional liturgy in favour of a discourse by Henley on all kinds of issues, with intervening prayers. The theology behind this performance was also far removed from that of the often tepid doctrines of the Anglican mainstream in which the minister had been raised, as they centred on a call to restore primitive Christianity, from which all later sects had deviated. Finally, the undertaking rested on an elaborate campaign of advertising in the London press. The writers of the Journal did not have to work very hard to find topics of ridicule, such as Henley’s shameless puffs for his own eloquence. Unlike most of the victims, he replied to their charges at frequent intervals in his own paper, The Hyp-Doctor, which he started just after the Journal first appeared.

It was rather the same with Curll. As early as the fourth issue, on 29 January 1730, we come on an application from a certain Kirleus to be appointed bookseller to the honourable society of Grub Street. In view of the record that the notorious publisher had assembled over the years, everyone might have anticipated that the choice would be a foregone conclusion, especially after Curll appended an election manifesto boasting of his achievements across the board: “Tho’ Biography, secret History, natural Philosophy, and Poetry were my chief favourites; yet no part of literature can complain that it has been disregarded” (all too true). However, in April we learn that the job has gone to Captain L. Gulliver, alias Lawton Gilliver. This does not preclude the columns of the Journal from returning obsessively to Curll in succeeding years. Often he is twinned with Henley, as the two men formed an advance guard of self-publicity. How closely the pair were linked can be seen in verses addressed in 1733 to the infamous murderer Sarah Malcolm, recently depicted by William Hogarth: “No Grubstreet Hack shall dare to use your Ghost ill; / Henley shall read upon your Post a Postill; / Hogarth shall transmit your charms to future Times; / And Curll record your Life in Prose and Rhymes.” A postill here means a sermon, perhaps delivered when Malcolm stood at the foot of the gallows (“post”) in Fleet Street.

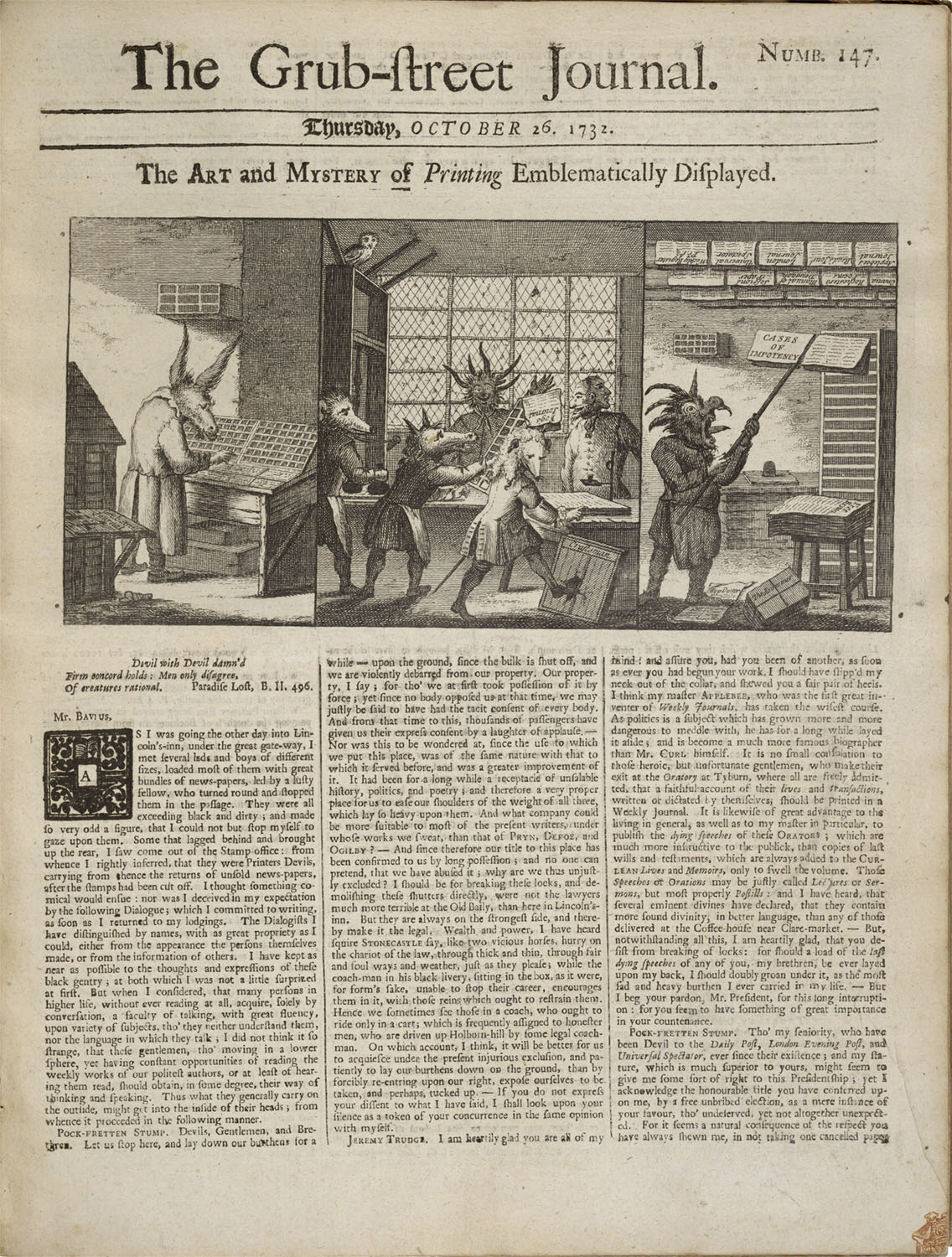

The most striking of all these attacks came in Journal on 26 October 1732. This contained a dialogue on “The Art and Mystery of Printing,” illustrated by an “emblematic design” showing a scene in a printing house, given fantastic allegorical interpretations. A strange Janus-faced figure stands at the heart of the design: “The grand figure I take to be a bookseller, who has as much occasion for two faces in the way of trade, as persons in any other business….He may be considered as giving directions to his authors, to write poetical, political, historical, theological, or bawdy books; which authors are properly represented by the gentlemen who have the heads of a dog, a horse, or a swine, and are accordingly treated by him like spaniels, hackneys, and hogs.” Another segment of the print shows a diabolic figure hanging up on a rack some proof sheets of Cases of Impotency: “The devil in the last division of the picture, seems to denote a particular bookseller, stripped of all his false ornaments of puffs, advertisements, and title pages, and in propria persona, putting up his own and other peoples copies, books, some of pious devotions, and others of lewd diversion, in his literatory.” In 1729 Curll had set up a Literatory, or Universal Library, in Bow Street. No need to specify who the particular bookseller might be.

The Grub-Street Journal 26 October 1732, courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA 4.0). |

Legacy

During its run, the paper made a notable contribution to public debate in the 1730s. This was despite some indications of a sag in its brio and energy during the final two years. Its remit was narrow and it disavowed, not altogether convincingly, any political intent. But it stands out in the history of English journalism as the first paper to combine orthodox news with a satiric meta-reportage built around quotations from rival titles. Russel’s preface to the republished Memoirs of the Society of Grub Street offers a rationale for the Journal’s approach, setting the war of the dunces in a historical timeline that goes back beyond the lapse of the Licensing Act in 1695. By these means, the Journal was able to provide a distinctive take on the cultural scene under George II. However, this commentary unavoidably consisted of fragments culled from the daily, weekly and monthly press, and so it comes nowhere near The Dunciad in terms of artistic coherence, narrative and dramatic development, or thematic richness. But that is to set a very high bar indeed.

The first four years of the paper have been reprinted, ed. Bertrand A. Goldgar, in 4 volumes (London, 2002). Most regrettably, the remaining volumes were omitted: although the Journal had fallen into a gradual decline by 1735, there is a considerable amount of valuable material in later numbers. See also James T. Hillhouse, The Grub Street Journal (1928; reprinted New York, 1967); and B.A. Goldgar, “Pope and the Grub-street Journal,” Modern Philology, 74 (1977), 366–80.