Vauxhall Gardens

Paul F. Rice, Memorial University of Newfoundland

November 2022

The pleasure gardens in Vauxhall were situated by the River Thames in the Borough of Lambeth, and about a mile south and opposite of Westminster. The Vauxhall Gardens were a later development of the New Spring Gardens, mentioned in the diary of John Evelyn (1620–1706) on July 2, 1661. Samuel Pepys (1653–1703) referred to an earlier enterprise as the Old Spring Gardens in his diary (May 29, 1662). On that occasion, he visited both the Old and New Spring Gardens and claimed that the latter “much exceeds the other” (The Diary of Samuel Pepys, 1970–83). The New Spring Gardens became a favourite haunt of Pepys (see his diary entries for June 23, 1665, and May 28, 1667) who records his enjoyment of breathing clean air, listening to the songs of nightingales and the pleasure of good company. Already at this time, the gardens contained walkways, bordered by trees and hedges. Although its Arcadian pleasures were not tempered by reality, they provided Londoners respite from the more unpleasant conditions of city life during the summer months. The area was accessible by boat from the Thames, and refreshments were available from nearby inns and taverns.

The development of the site as a modern pleasure garden began on 17 March 1729 when Jonathan Tyers (1702–67) leased the ground from Elizabeth Masters (proprietor and copyholder under the Prince of Wales’s Duchy of Cornwall Estates) for thirty years at a rate of 250 pounds annually. By this time, the gardens had been enlarged and the lease mentions various buildings and numerous walkways and seating areas. David Coke and Alan Borg suggest that the enterprise was already “well-organized and quite elaborate, ... providing a good basis for the developments that Tyers was to undertake” (Vauxhall Gardens: A History, 2011). Tyers soon transformed an area which had become a place frequented by prostitutes into a place which elevated the spirit through music, the visual arts, refined company and the experience of nature.

The frequent presence of Frederick, Prince of Wales, did much to encourage an atmosphere of optimism and youthful energy. Tyers encouraged Frederick’s patronage and had a pavilion built for the prince’s comfort. This was open on one side so that he and his entourage could enjoy the concert, but was elevated sufficiently to prevent unwanted intrusions. Frederick was being groomed to become a “Patriot King” by a group influenced by the liberal ideology of Henry St. John, Viscount Bolingbroke (1678–1751). Such a king would devote himself to the welfare of Britain and not allow foreign interests to influence his rule. Although Vauxhall became, by extension, a centre of the Politics of Opposition, Tyers could never openly embrace such views without alienating an influential segment of his potential audience base. Still, an anti-establishment atmosphere could be detected. As David Coke and Alan Borg write:

From the 1730s until the early 1750s Vauxhall Gardens formed the epicenter for that creative reaction of youth against authority which has been seen as the English expression of the Rococo style. This rebellion, embodied at Vauxhall in the patronage of Frederick, Prince of Wales, the paintings of William Hogarth and Francis Hayman, the sculpture of Louis François Roubiliac, the music of Thomas Arne and George Frideric Handel, and the designs of Hubert-François Gravelot and George Michael Moser, reflected the libertarian attitudes and enlightened management style of Jonathan Tyers. The brash light-heartedness, the unwillingness to follow rules, the energy, informality and experimentation that were intrinsic to Vauxhall are all typical of the English Rococo; this intoxicating cocktail enhanced every evening’s excitement, and put Tyer’s visitors in the right frame of mind to enjoy themselves, to refresh their spirits and to spend their money.

Vauxhall Gardens: A History, 2011.

Tyers was influenced in his efforts by William Hogarth (1697–1764) who encouraged the manager to present an uplifting moral message to his patrons. George Frideric Handel (1685–1759 and John James Heidegger (1666–1749) influenced the development of a strong musical programme for the gardens, while Francis Hayman (1708–76) designed the allegorical and morality paintings in the fifty-plus supper boxes that had been constructed in the colonnades bordering the Grove where musical performances took place. Handel’s music figured prominently in the programmes at Vauxhall and his presence on the grounds was both literal and virtual. A life-sized statue of Handel was created by Louis Francis Roubiliac (?1695–1762) and unveiled in 1738 in a prominent place in the Grove. In 1749, Tyers went to great lengths to obtain a public rehearsal of Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks on April 21, 1749. Handel’s own reservations were discounted once Tyers offered the organizers of the Green Park premiere the use of many lamps and lanterns, and thirty of his staff to assist at the event. Who could refuse such an offer? The rehearsal was a publicity coup of the grandest proportions and the audience numbered in the thousands, causing severe traffic jams on all of the streets leading to Vauxhall. The rehearsal was more successful than the later performance in Green Park on April 27, 1749, when the planned fireworks misfired and injuries resulted to several people.

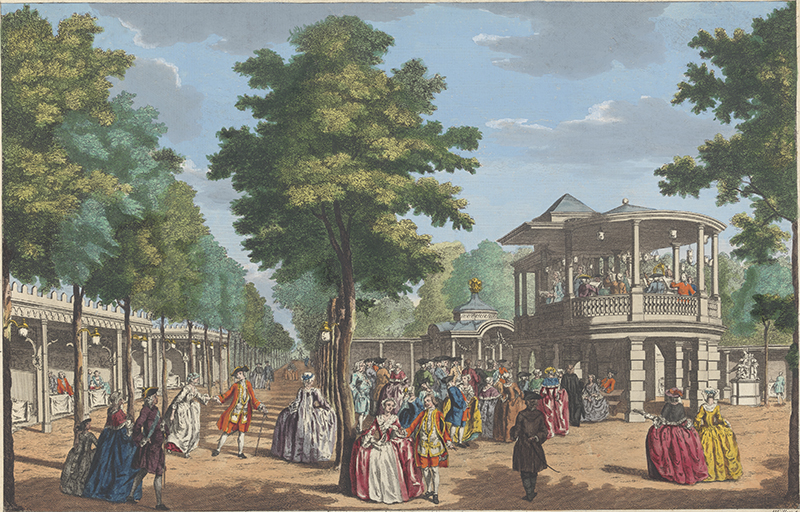

In 1735, Tyers had a large, cylindrically-shaped structure, known as the Orchestra, built in the Grove. The musicians were elevated above the heads of patrons which likely allowed for the music to be heard for greater distances. An orchestra of skilled players was engaged to give nightly concerts. The Daily Advertiser (June 2, 1735) announced that the group would include “finest Instrumental Performers; who will play (beginning at Five every Evening during the Summer Season) the compositions of Mr. Handel, and other celebrated Masters.” A structure adjacent to the Orchestra was constructed in 1737 which housed a powerful pipe organ. These buildings were painted by Giovanni Antonio Canaletto (1697–1768) ca. 1751. Both structures were demolished during the winter of 1757–58 to make way for a single building that contained the pipe room and space for up to fifty performers. Known as the Gothic Orchestra, it served until the gardens closed in 1859.

Tyers followed the lead of Cuper’s Gardens and those at Marylebone by introducing vocal music to the concerts 1745. This was risky in an out-of-doors setting before modern amplification, but the use of baffles likely assisted in projecting the singers’ voices. He hired Thomas Augustine Arne (1710–78) that same year to provide suitable vocal music for the concerts and three famous singers, including Arne’s wife Cecilia (1712–89). These singers added much prestige to the concerts. Tyers may not have been the first to introduce vocal music in an outdoor setting, but he was seemingly determined to be the most successful at it. The painting by Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827), Concert at Vauxhall Gardens (ca. 1784), shows the famous soprano Frederika Weichsell (d.1786) performing for the crowd gathered below.

By the 1740s, the routine of an evening at Vauxhall was well established. Entrance of one shilling permitted anyone who was suitably dressed, regardless of class, to enter. Season passes were also available. This scenario was not quite as egalitarian as it might initially seem. Servants in livery were not permitted, and a shilling was too expensive for many people to afford. Still, people from various classes could enjoy the same entertainments in an informal setting. Once inside, patrons could order a meal of cold meats and salads which would then be delivered to their assigned supper box or a garden table. Patrons were free to wander the grounds and enjoy nature in the Grand Walk and the Italian Walk located beyond the Grove. A further area, known as the Dark Walk, bordered Kennington Lane and was not appropriate for young ladies to venture down unescorted. While Tyers was diligent in maintaining a high moral standard in the gardens, stories of opportunistic men attempting to seduce women were common. Fanny Burney (1752–1840) described the phenomenon in her novel Evelina. Tyers would have been well aware that the suggestion of sexual freedom was a significant attraction for the younger generation; however, lewd conduct could not be tolerated. One of the most eagerly anticipated events each evening was the lighting of the lamps in the Grove. In an era before electricity, lighting around 1,000 oil lamps would have been a slow process. A great innovation from the 1740s was to link of all of the lamps with cotton-wool fuses. This resulted in the gardens being illuminated within two minutes. If not quite instantaneous as many commentators described, it was still a noteworthy effect for the time.

The formal concert presented in the Orchestra, as opposed to the strolling musicians in the gardens, began around five p.m. in the early days of the gardens. This was because of the limited capacity of the oil lamps that provided illumination after dark. By the 1750s, technology had improved so that the gardens could remain illuminated to around midnight. The formal concerts then began around eight o’clock to please the tastes of the aristocracy. Knowledge of the concert programmes comes from later in the century. They reveal that the concerts featured concerti (organ concerti were a nightly occurrence), symphonies and vocal pieces. The following is taken from the London newspapers for 14 July 1787:

| Vauxhall Concert Programme for 14 July 1787 | |

|---|---|

| Act I | |

| Full Overture, | [K.F.] Abel |

| Overture to The Syrens, | [J. A.] Fisher |

| Song, (sung by Mr. Incledon), | ?James Hook |

| Symphony, | [Thomas] Shaw |

| Overture to Berenice, | G.F. Handel |

| Song, (Miss Bertles), | ?James Hook |

| Symphony, | [F.J.] Haydn |

| Organ Concerto, | ? |

| Song, (Miss Leary), | ?James Hook |

| Act II | |

| Song, (Mr. Incledon), | ?James Hook |

| Glee,& | [?S. ]Webb |

| Catch, | James Hook |

| Song, (Miss Bertles), | ?James Hook |

| The Queen of May [Finale], | James Hook |

The organ concerto would have been performed by Hook, although whether or not he composed it is open to conjecture.

Inclement weather was the bane of all public gardens and Vauxhall was no exception. In 1742, Tyers erected three temporary buildings to accommodate patrons when it was either too cold or too wet to enjoy being outside. He took this a step further for the opening of the 1748 season by erecting the circular Rotunda with its highly ornate fan-like ceiling. This structure was likely influenced by the similar structure at Ranelagh, but was about half the size. Still, the musicians and patrons could enjoy concerts in comfort when being outside was unpleasant.

Tyer’s careful management of the enterprise resulted in its being financially successful. In 1752, he purchased half of the estate and six years later, the second half. The land was still not freehold, but the property could now be passed on to his children following his death in 1767. His second son, also called Jonathan (1729–92), managed the gardens for the next 25 years during which time there were few innovations and the enterprise began to decline. Bryant Barrett (1743–1809, Jonathan Jr.’s son-in-law) took over the management in 1792. He must have been acutely aware that the London pleasure gardens were beginning to pass out of favour. Marylebone had already closed and Ranelagh would soon follow. Visitors to Vauxhall now wanted more excitement and greater novelty in their entertainments. Barrett achieved this by introducing firework displays created by Michael Hengler (d. 1802) and his wife. The introduction of exotic foreign musicians and military bands catered to the taste for novelties. All of this was costly and Barrett increased the cost of admission to two shillings for the 1792 season.

Barrett took full advantage of the recent craze for ballooning, with their introduction in 1802 being highly successful. Spectators thronged to view the ascents and, by mid-century, the balloonist Charles Green (1785–1870) was able to include passengers. After 1816, there was a radical change in the entertainments on offer, with the appearance of acrobats and tightrope walkers being more in line with circus events. Tyer’s descendents gave up on the gardens in 1821 and leased it to a business consortium. An advertisement found in The Age (1 August 1830) gives a sense of the types of entertainments on offer:

The amusements will consist of the Concert, Vaudeville, Cosmoramas, Fantoccini, Fireworks, &c.; and conclude with the GRAND MOVING HYDROPYRIC PANORAMA, which is allowed to be the most magnificent spectacle ever produced in this or any other country. The Vaudeville will commence at Half-past Nine.

The atmosphere appears to have become increasingly circus-like as the managers tried to compete with the entertainments offered at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre and Astley’s Amphitheatre. The gardens closed for the last time on 25 July 1859, but their history bears witness to one of the most celebrated pages in the social history of London.

A View of the Chinese Pavillions and Boxes in Vauxhall Gardens, after 1751, by Thomas Bowles (1712–53). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.18706. Public Domain. |

The Inside of the Elegant Music Room in Vauxhall Gardens, 1751, by Henry Roberts (ca. 1710–1790). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.18708. Public Domain. |

Vauxhall Gardens, ca. 1784, Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1975.4.1844. Public Domain. |

A View of the Temple of Comus & c. in Vauxhall Gardens, ca. 1794, by John S. Muller (ca. 1715–1792). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.18715. Public Domain. Public Domain. |

Vauxhall Garden, by John Bluck (active 1791–1831) after Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.18697. Public Domain. |