White Conduit House

Paul F. Rice, Memorial University of Newfoundland

November 2022

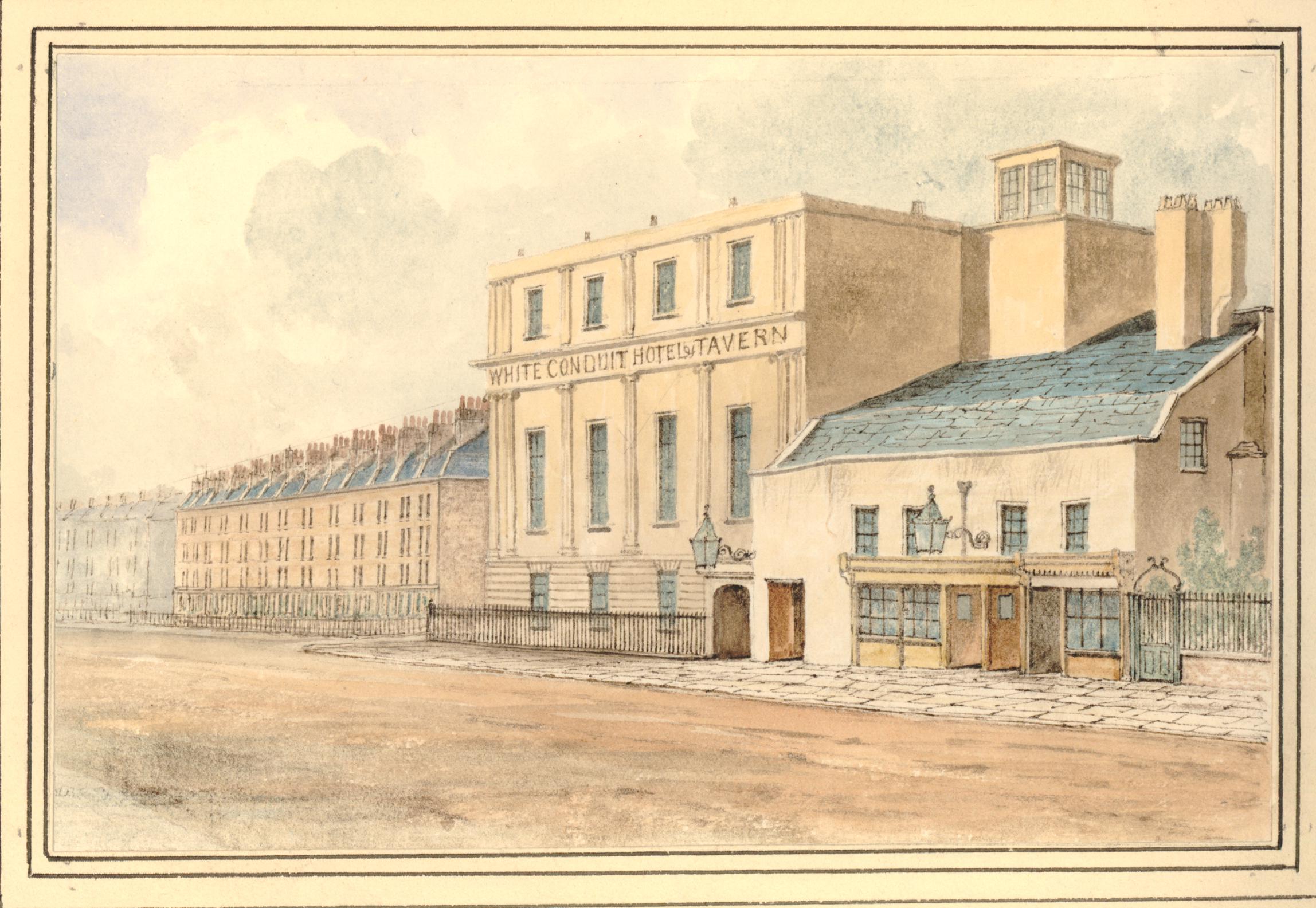

Not all of the pleasure gardens of London aspired to attract the highest echelons of society. Some, such as the White Conduit House, were happy to attract the working classes. Given that this social demographic was larger than that of the aristocracy, the choice may have contributed to the longevity of the enterprise. Located in Islington near the corner of Barnsbury Road and Dewey Road in present-day London, the site was decidedly rural during the early days of the eighteenth century. The name of the enterprise was taken from a water conduit faced with white stone in a nearby field. This conduit had supplied water to the area from the New River since the 1400s. Although the White Conduit House was only a small alehouse in the seventeenth century, a larger structure had been erected by 1745 containing a Long Room for the greater pleasure of patrons. At the same time, the gardens were laid out to include a circular fish pond and gravelled walks with pleasant arbours for those who wished to partake of their beverages in the fresh country air. During the proprietorship of Robert Bartholomew (beginning in 1754 and continuing until his death in 1766), the outdoor activities were expanded to include cricket in the adjoining meadow. The enterprise differed from most other pleasure gardens in London in that the tavern also offered hotel accommodation. There must have been a demand for this since the hostelry side of the business was expanded in 1829 when the new White Conduit House was built.

During the eighteenth century, the White Conduit House became known as much for the refreshment on offer as the rural beauty of its surroundings, with the tavern providing hot loaves, tea, coffee and various liquors. Although Coke and Borg described the enterprise as “barely respectable” (Vauxhall Gardens: a History, 2011), it was likely more than that and Oliver Goldsmith writing in his Citizen of the World (Letter CXII) commented that the inhabitants of London often assembled there to enjoy a feast of hot rolls and butter. The business appears to have made its money from the sale of such refreshments and any admission fee during the eighteenth century was nominal. Even in the nineteenth century, the admission fees appear to have been regulated by nature of the entertainments being offered and varied from six pence to half a crown.

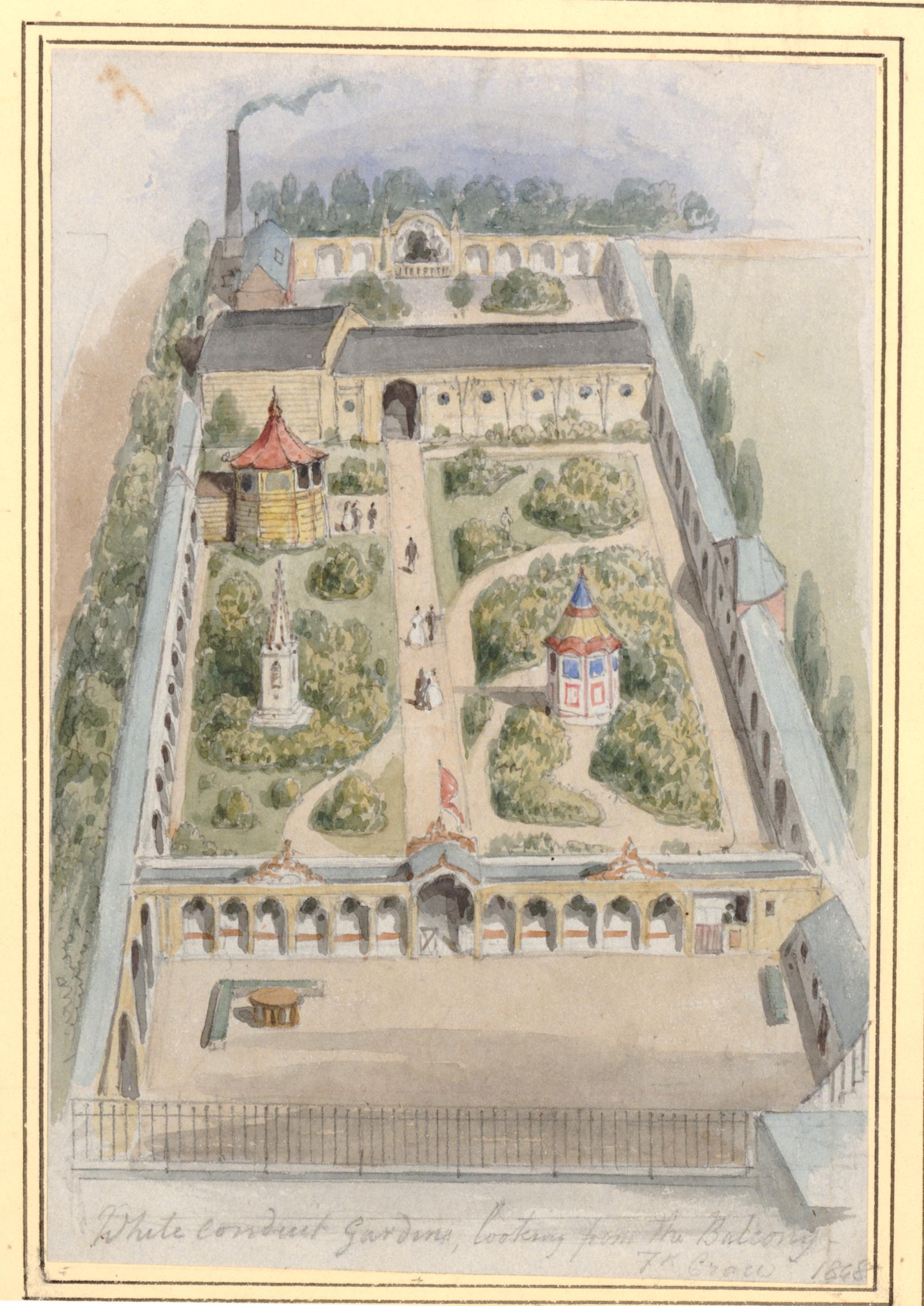

Until the end of the eighteenth century, musical performance at the White Conduit House was restricted to the organ installed in the Long Room. James Hook was engaged as the organist shortly after he moved to London from Norwich in 1764. He performed daily for the pleasure of the patrons, but when the position of organist became available at the prestigious Marylebone Gardens in 1768, he left the White Conduit House. The tavern’s building was expanded during the early years of nineteenth century to make room for dancing and billiards. The arbours and tea boxes were enlarged, a maze planted, and bowls and archery were added to the outdoor activities. A bandstand and stage area was erected in the gardens by 1825 to accommodate performances of singers and instrumentalists. At that time, musical entertainments became more frequent and the proprietor took to advertising the enterprise as the “New Minor Vauxhall,” although neither the quality of the orchestra nor the renown of the vocal soloists competed directly with those heard at the concerts of the Vauxhall Gardens.

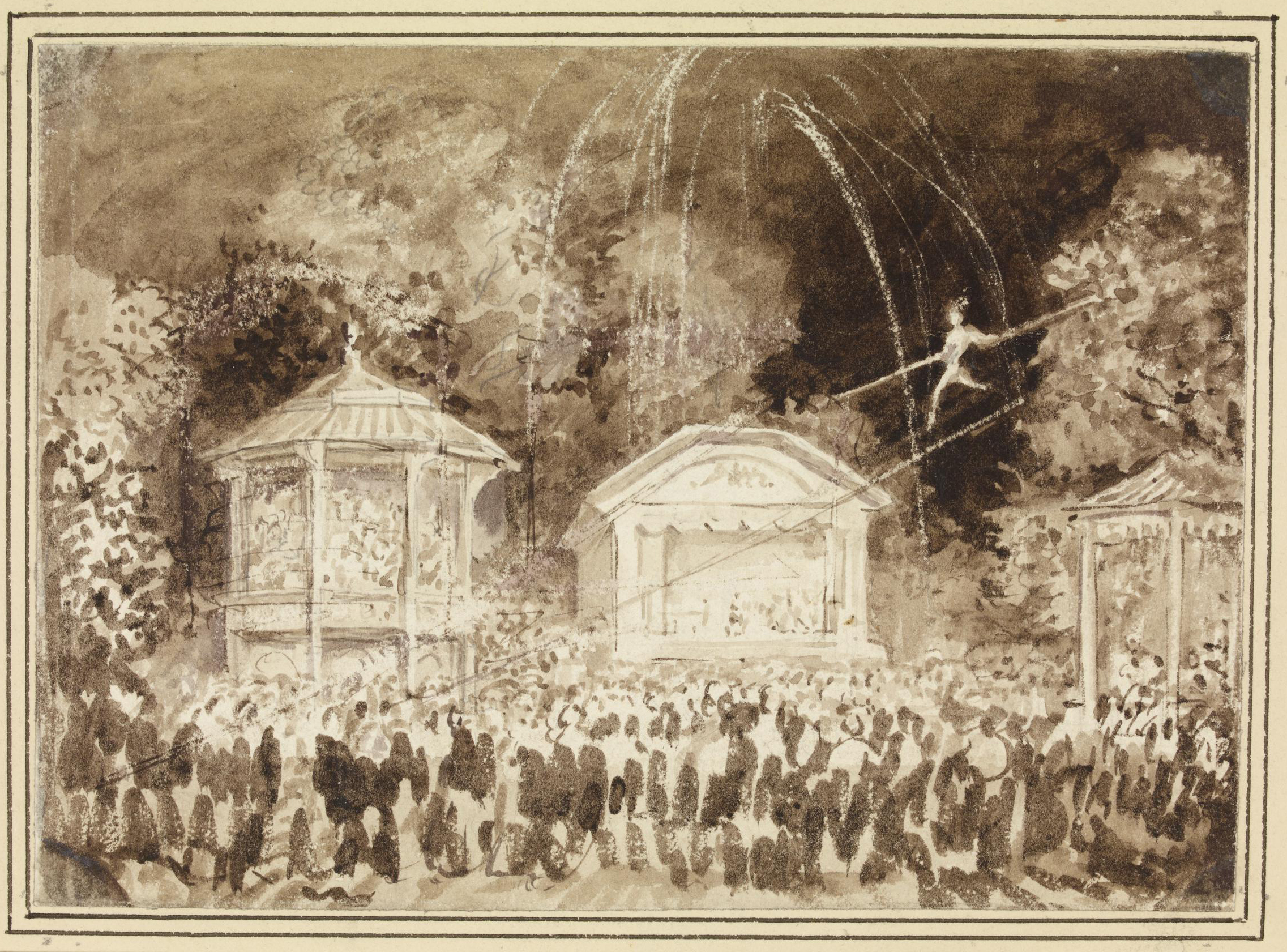

While the White Conduit House was never as fashionable as Vauxhall, both locations found it difficult to attract audiences after 1830 and compensated with entertainments that were increasingly circus-like. At the White Conduit House, this meant presentations of jugglers, fire-eaters, fireworks and balloon ascents on a regular basis. With time, the rural location of the enterprise was endangered by the encroachment of the ever-growing metropolis. The once pleasant rural views of meadows and fragrant hay fields disappeared, to be replaced by the sight of road building and houses under construction. Instead of fragrant country breezes wafting over the fields, there were now fumes emanating from the smoke stack of a coal-gas production facility located at the edge of the property. Warwick Wroth writes that “the amusements of White Conduit House gradually deteriorated, until they were terminated on 22 January, 1849, by a Ball given for the benefit of the check-takers. Three days afterwards the demolition of the house was begun, and it was soon levelled for a new line of streets” (The London Pleasure Gardens, 1896). Such are the costs of progress.

White Conduit House, 1848. British Museum 1880,1113.5016. © The Trustees of the British Museum. This image is provided under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. In certain other jurisdictions it is considered to be in the public domain. |

Bird's eye view looking over the gardens of the White Conduit House, 1848, by Frederick Crace. British Museum 1880,1113.5018. © The Trustees of the British Museum. This image is provided under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. In certain other jurisdictions it is considered to be in the public domain. |

White Conduit House Hotel and Tavern, 1849, by C.H. Matthews. British Museum 1880,1113.5017. © The Trustees of the British Museum. This image is provided under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. In certain other jurisdictions it is considered to be in the public domain. |