Lincoln's Inn Theatre

Names

- Lincoln's Inn Theatre

- Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre

- Lisle's Tennis Court

- the Duke of York's Playhouse

Street/Area/District

- Portugal Street

Maps & Views

- 1658 London (Newcourt & Faithorne): Lisle's Tennis Court

- 1660 ca. West Central London (Hollar): Lisle's Tennis Court

- 1720 London (Strype): Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre

- 1736 London (Moll & Bowles): Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre

- 1746 London, Westminster & Southwark (Rocque): Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre

Descriptions

from London Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions, by Henry Benjamin Wheatley and Peter Cunningham (1891)

Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre stood in Portugal Row, or the south side of Lincoln's Inn Fields, at the back of what is now the Royal College of Surgeons. There have been three distinct theatres called "Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre;" all three erected on the same site, and all of interest in the history of our stage. The first was originally "Lisle's Tennis Court,"1 converted into a theatre (The Duke's Theatre) by Sir William Davenant, and opened in 1660, "having new scenes and decorations, being the first that e're were introduc'd in England."'2 Pepys went to "the new play-house," November 20, 1660, and saw Beaumont and Fletcher's Beggar's Bush and Mohun (or, as he writes it, Moone) play for the first time: "it is the finest play- house, I believe, that ever was in England." Pepys's references to the Lincoln's Inn Theatre are very numerous: indeed he went there so often that it made Mrs. Pepys "as mad as the devil." Davenant died in April 1668, and Pepys went on the 9th to "the Duke of York's Play-house, there to see Sir W. Davenant's corpse carried out towards Westminster, there to be buried." The company continued at the Duke's till November 9, 1671, when they removed to Dorset Gardens, and their old house in Lincoln's Inn Fields remained shut till February 26, 1671-1672, when the King's company under Killigrew, burnt out at Drury Lane, made use of it till March 26, 1673–1674, when they returned to their old locality in Drury Lane, and Davenant's deserted theatre became "a tennis court again."3

The second theatre on the same site ("fitted up from a tennis-court"4) was built by Congreve, Betterton, Mrs. Barry, and Mrs. Bracegirdle, and opened April 30, 1695, with (first time) Congreve's comedy of Love for Love. William III. was present, and there was a large and splendid audience. The epilogue, which was spoken by Mrs. Bracegirdle, wound up with an allusion to this circumstance:—

And thus our Audience which did once resort

To shining theatres to see our sport

Now find us toss'd into a Tennis Court,

These walls but t'other day were filled with noise

Of roaring gamesters, and your Damme Boys;

Then bounding balls, and rackets they encompast,

And now they're filled with jests, and flights, and bombast.

Cibber speaks of this theatre as "but small and poorly fitted up within. Within the walls of a tennis quaree court, which is of the lesser sort."5 Christopher Rich, in the year 1714, took down this makeshift house, and "rebuilt it from the ground," says Cibber, "as it is now standing."6 He did not live, however, to see his work completed; and this, the third theatre on the same spot, was opened (December i8, 1714) with a prologue, spoken by his son, John Rich (died 1 761), dressed in a suit of mourning. John Rich's success in this house was very great. Here he introduced pantomimes among us for the first time—playing the part of harlequin himself, and achieving a reputation that has not yet been eclipsed. Here Quin played all the characters for which he is still famous. Here, January 29, 1727–1728, the Beggar's Opera was originally produced, and with such success that it was acted on sixty-two nights in one season, and occasioned a saying, still celebrated, that it made Gay rich and Rich gay.7 Here Miss Lavinia Fenton, the original Polly Peachum of this piece, won the heart of the Duke of Bolton, whose Duchess she subsequently became; and here Fenton's Mariamne was first produced. Rich removed from Lincoln's Inn Fields to the first Covent Garden Theatre, so called in the modern acceptation of the name, on December 7, 1732.

The house in Portugal Street was subsequently leased for a short time by Giffard, from Goodman's Fields; and in 1756 was transformed into a barrack for 1400 men. It was afterwards Spode's and then Copeland's China Repository, and was taken down August 28, 1848, for the purpose of enlarging the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons. The principal entrance was in Portugal Street.

1 Indenture signed by Sir W. Davenant, dated March 7, 1660–1661 (in possession of author); Aubrey's Lives, voL ii p. 308; Pepys says, "which was formerly Gibbon's tennis-court."

2 Downes's Ros. Ang., ed. 1708, p. 20.

3 Aubrey's Lives, vol. ii. p. 309.

4 Downe's, p. 58.

5 Cibber's Apology, e. 1740, p. 254.

6 Cibber's Apology, e. 1740, p. 352

7 There is at Mr. Murray's [see Albermarle Street] a capital picture by Hogarth of a scene in the Beggar's Opera, consisting

from The Commonwealth and Restoration Stage, by Leslie Hotson (1928)

Lisle's Tennis Court

Another tennis court, also near Lincoln's Inn Fields and not two hundred yards from Gibbons's, was destined to eclipse the latter in importance and fame as a playhouse. As Gibbons's was the last of the old order, so Lisle's was the first of the new—the first regular theatre to use movable scenery." Dave- nant's opening of Lisle's Tennis Court late in June, 1661, as the Duke's Playhouse, was, in Mr. Lawrence's phrase, an event truly epoch-marking.94

Strange that our students of the theatre have discovered neither the beginnings nor yet the physical arrangement of a playhouse which stood as the first chapter in the history of the modern stage! A hope of filling part of such a reproachful gap impelled me to a rather laborious search, the fruits of which are here brought together for the first time.

The story95 begins on 14 June, 1656, when Sir David Cunningham, Bart., of London, for £120 sold to Horatio Moore, Esq., of Lincoln's Inn a half-interest in a piece of ground in Lincoln's Inn Fields. It is described as

part and parcel of the said fields called Fickett's, Purse Field, and Cup Field, or one of them, adjoining on the east side to a great messuage or tenement, stables or other buildings there, then or then late of Sir Basil Brooke's, knight, wherein Thomas, Lord Brudenell then inhabited or dwelt ... which ... contains in breadth from west to east on the south side of the said great messuage and building seventy-three foot of assize or thereabouts all along from the said great house, stables, and buildings by the verge or edge of the causeway leading from the New Market place towards Lincoln's Inn; and ranging from west to east on the north side from the front of the said great messuage towards Lincoln's Inn Wall, seventy-three foot also of assize or thereabouts, and extending in length or depth from the edge or verge of the aforesaid causeway to the front or range of the said Sir Basil Brooke's house.

Six weeks later Cunningham sold Moore half of another plot, next to the foregoing and extending another 45 feet eastward toward Lincoln's Inn Wall. The other half-estates in these two pieces of ground were sold to one James Hooker, gentleman, of St. Clement Danes.

On the surface these transactions are simple enough. But it comes out that the real purchasers behind Horatio Moore were his mother-in-law, Anne Tyler of Fetter Lane, and her new husband, Thomas Lisle, Esq. Lisle's name appeared nowhere in the business, and even his marriage with Anne Tyler was concealed for some years, we are told, because he was "obnoxious to the powers" (that is, Cromwell's government) as a former servant to the King.

Shortly after the sale was completed, Anne Tyler and James Hooker began to build on their ground "all that tennis court ... afterwards converted into a playhouse and commonly called the Duke's Playhouse ... and two little tenements adjoining on the north part, and several little shops on the south part."

Their operations elicited a protest from the Council of the Society of Lincoln's Inn, in the shape of an order, 5 November, 1656, "to have an informacion drawne against James Hooker and Anne Tyler for the newe buildings in Lincolne's Inne Fieldes, intended for a rackett courte."96 Yet we read that on 4 February, 1657, the Council was ready to receive "proposicions ... from James Hooker and Anne Tyler concerninge the new building in Lincoln's Inne Fields, intended for a tennis Court."97 Whatever the propositions may have been, no prohibitive action was taken by the society, and construction went forward, so far as we know, without serious interruption. We may suppose that the building was completed late in 1656 or early in 1657.

Moore made a written declaration on 27 June, 1657, that all the money he spent for the land and the buildings was Lisle's, and that his (Moore's) name was used in trust for Lisle. Up to this time Moore was only a lay figure. He entered actively into the business, however, when he bought out Hooker's half-interest in the ground and buildings on 28 March, 1658, for £500. A month later he granted a lease of 1000 years in this half-interest to Lisle, at a rent of £20 a year. Lisle, already owner of half the property, thus obtained a long-term lease of the remainder.

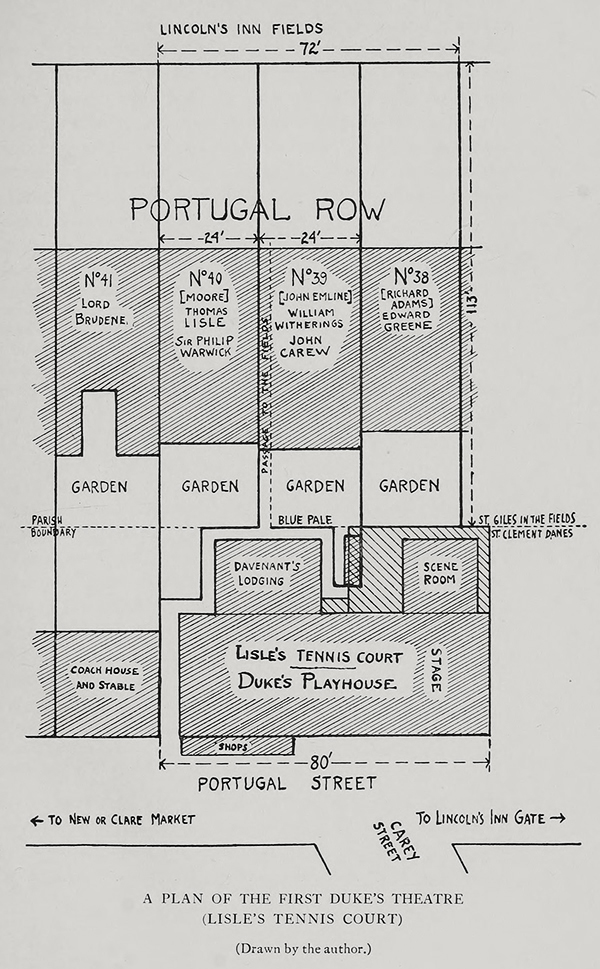

The tennis court was built along the south side of the ground and stood next to Lord Brudenell's coach-houses. The northern part of the ground abutted west on Lord Brudenell's dwelling, which stood at the eastern end of the half-finished Portugal Row. All this is made perfectly clear by a glance at the plate facing page 128. This is the splendid view by Hollar, containing a representation, hitherto unidentified, of Lisle's Tennis Court, as it was in 1657. There it stands, with open ground on three sides, between Lincoln's Inn Fields and Lesser (or Little) Lincoln's Inn Fields. People are rambling in the fields; clothes are being spread on the grass to dry. A few yards to the south of the court, a coach has pulled up at the door of the Grange Inn, where Davenant's players used to come and drink after the performance. The scene would be completely peaceful if one of London's trained bands were not using the Fields as a drill ground. Couples are strolling by the Tennis Court along what was first called the Causeway, which leads between the coach-houses and the burying ground of St. Clement Danes parish to New or Clare Market. Strype described this street as follows: "On the Back side of Portugal Row, is a Street which runneth to Lincoln s Inn Gate, which used to pass without a Name, but since the Place is increased by the new Buildings in Little Lincoln's Inn Fields, and the Settling of the Play House, it may have a Name given it, and not improperly, Play-house Street."98 This quotation is from the 1720 edition of Strype's Stow. By 1755 the name had been settled as Portugal Street,99 which it is to-day.

To return to Lisle's, the "two houses that adjoin and lean upon the north wall of the new tennis court" are plainly shown in the view, by the gables projecting beyond the roof of the court. I shall have more to say of these later. The shops on the south side are not represented in the engraving.

As to the dimensions of the court, a clue to its length is found in the assignment by Anne Tyler and Horatio Moore of a "parcel of ground in Pickett's Field containing 180 feet in length from the house then in the occupation of Lord Brudenell eastward and from the utmost south bounds of Cup Field aforesaid to the pales then before the said Tennis Court, and from the east end of the said Tennis Court, 100 feet." Subtraction gives 80 feet as the distance from Lord Brudenell's buildings to the end of the court. If we allow five feet for the passage between, indicated in Hollar's view, we then have 75 feet as the length of the building; which is shorter than the average length for a standard court. Julian Marshall100 gives 100 English feet as the usual length of a quarrée court. Our conclusion that Lisle's is shorter than this is corroborated by Cibber's remark, referring to Lisle's as "a Tennis Quaree Court, which is of the lesser sort."101 The width must have been about 30 feet. I have tried to indicate these matters in the sketch plan facing page 124.

To be able to follow the later history of the court, we must turn for a moment to consider the building of houses which now took place in Portugal Row, north of the court.

Acting for Lisle, Horatio Moore on 26 February, 1657/8, bought from Sir William Cowper and two others a part of Cup Field

... extending on the west part from the outermost eastern post of the rails before the brick house then ... in the tenure ... of the Lord Brudenell, 124 Commonwealth and Restoration Stage standing at the west end of the southern long row or range of building in the Fields called Lincoln's Inn Fields and from thence in front extending seventy-two foot of assize straight on eastward from the said post ... towards Lincoln's Inn ... and from the said front running southward hence into the said field called Fickett's Field, containing by estimation one hundred and thirteen foot.

This 72-foot frontage was divided into three lots of 24 feet each. For a knowledge of the houses built here, I am indebted to the recent penetrating researches of Mr. W.W. Braines, carried out for the London County Council Survey of London.102 Following Mr. Braines, I have numbered the lots on the sketch plan according to the present numbering of the houses on their sites. Upon Number 40, next to Lord Brudenell's, Moore built a house with Lisle's money before 12 November, 1658. On the latter date he sold to John Emline of "St. Martin's in the Fields ... Brickmaker," the site of Number 39, measuring 24 by 127 feet, abutting east on the site of Number 38 (sold to one Adams), and south "upon the blue pale within four foot of the house on the north side of the Tennis Court."103 A reservation was made to Moore and his assigns and the tenants of the Tennis Court of the use of a passage to be left at the east or west end of the plot, at least 3 feet, 3 inches in width and one story high, to go through the building as far as the "blue pale." This passage had an extraordinarily long life. It is found in exactly the same position on Rocque's map of London (1746), connecting the theatre with Lincoln's Inn Fields. Emline, in the course of 1659, erected a house on the site of Number 39, and sold the premises 3 December, 1659"104 to William Witherings, Esq. In the deed he explains that the passage aforesaid had been formed on the "west end ... as an alley to pass into and from Lincoln's Inn Fields." He also tells us that by this time Richard Adams had made over the next plot on the east (Number 38) to one Edward Greene, who had built a dwelling on it.

Affairs were in this posture when Davenant came on the scene. At the end of March, 1660, he contracted with Lisle for a lease of the Tennis Court"105 to be converted into a theatre; and by the following winter he had made good progress in altering the building. But he found the necessary enlargement on the north side cramped by the wall and ground of Number 39, which, meanwhile, Witherings had leased to one John Carew in July, 1660. As Davenant puts it, "there wanted room for the depth of scenes in the ground belonging to the said Tennis Court; and therefore for accommodation for the said scenes your Orator did take a lease of John Carew, gent., of certain ground which he ... held in lease adjoining to the said Tennis Court." Dated 16 January, 1660/1, Carew's lease granted to Davenant

all that part of the brick wall ... on the east end of the then garden and backside of the said John Carew in Portugal Row ... and four foot of ground from the said wall westwards into and part of the said garden or backside, with free ingress, egress, and regress for ... [Davenant] ... his workmen and assigns to enter into the same garden or backside to build upon the same wall and four foot of ground; and at the end of the said lease (which was to continue for twenty years) again to pull down the same to the intent to re-erect the said wall and to make it as it was ... yielding and paying every year ... [Davenant] should use Representations [that is, present plays] in the said theatre to the said John Carew ... £4 per annum.

I have indicated on the sketch plan this encroachment of Davenant's on Carew's wall and garden. Obviously the little house at the eastern end of the court must have been chosen for this enlargement to give space for scenery, since Davenant's invasion was from east to west. Furthermore, this fixes the location of the Duke's Theatre stage at the eastern end of the building. In the process of enlargement, the little house was sacrificed. From an indenture of 7 March, 1660/1,106 I extract the following passage:

Sir William Davenant hath taken a lease of ... Lisle's Tennis Court ... and of two houses or tenements thereunto next adjoining ... one of the which said houses is since demolished for the better enlarging and convenient preparing of the said theatre there and in the Tennis Court.

After Carew had agreed to let Davenant break down the wall and encroach on the garden, he found that he had thereby thrown himself open to an action of waste on the part of Witherings, the owner. To avoid difficulty, Carew brought about an agreement, 14 February, 1660/1, between Witherings, Davenant, and himself, by which Witherings agreed not to sue them on condition that Davenant within three years after date "should throw down and remove the said wall so by him erected, and erect and build a new house of office in the same place where the house of office formerly stood, in such manner and as substantially as they were." Davenant was under bond of £200 to carry out this agreement.

All went well until the autumn of 1663, when Sir William was making preparations to throw down the wall and retire from the encroachment. Unfortunately, it appears that Carew had meanwhile sold his lease to William Walker, a goldsmith, who asserted that when he bought the lease he had "a peculiar respect" to the annual £4 which Davenant had agreed to pay Carew for the bit of garden. Still having an eye to the £4, he therefore wished Davenant's scene-house to stay partly in his garden, and even threatened action of trespass, and suit for the rent, if Davenant attempted to take it away. Witherings, however, insisted on his agreement to restore the status quo prius. Davenant was willing to fulfill it, but had no wish to be sued by Walker. Such was the muddle presented to the Court of Chancery. On 19 February, 1663/4, the court held that things should stand as they were until the following term, Davenant agreeing to indemnify Witherings for any damages he might sustain by Davenant's not "demolishing and new building" according to agreement. I have been unable to discover any further proceedings in the cause, and cannot tell whether Davenant ultimately narrowed his scene-house or left it as it was.

On the plan, I have represented a passage from the scene-house to the other of the two houses: a passage which I suppose must have been made, since the other house was Davenant's lodging as master of the theatre. Here he died in 1668, and of his funeral Pepys writes: "I up, and down to the Duke of York's playhouse, there to see, which I did. Sir W. Davenant's corpse carried out towards Westminster, there to be buried."107 Aubrey (i, 208) notes that "the tennis court in Little Lincoln's-Inne fields was turn'd into a play-house ... where Sir William had lodgeings, and where he died. ... His body was carried in a herse from the play-house to Westminster-Abbey."

Three years and a half after Davenant's death, his Duke's company moved to their sumptuous new theatre in Dorset Garden, opening 9 November, 1671. In the January following, the King's company, driven from their theatre in Bridges Street, Drury Lane, by a disastrous fire, took quarters in Lisle's Tennis Court, where they played for two years. On their departure, the building had to revert to its first use as a tennis court. To raise money for putting the court back into its old shape. Lisle made over half of his estate to his son-in- law, Richard Reeve. Before 1676 the latter had put £500 into "melioration" and repairs. He rebuilt "one of the said two tenements adjoining to the same Northwards [that is, the former scene-house] and the sheds or shops adjoining to the said tennis court southwards."

Tennis court it remained until Betterton's seceding company metamorphosed it once more into a playhouse in the spring of 1695. For a decade the old house again sheltered the drama. In 1714, after another considerable interval, Christopher Rich, who had been forced out of the control of Drury Lane, hired Lisle's at a low rent, and set about rebuilding it as a theatre. Although he died before the opening, his son John Rich took over the management; and it was this house which in 1728 saw the historic first production by Rich of John Gay's Beggar's Opera. The very success of the piece, however, doomed the playhouse; for Gay, newly rich, and Rich, newly gay, moved to a new and more capacious theatre in Covent Garden.

The old building was still standing in 1813, in use as a china warehouse. But during the last century it was swept away with others to make room for the present Museum of the College of Surgeons."108 It is somewhat lugubrious to reflect that on the spot where Betterton once delivered the lines of Hamlet, which anatomize the human soul, we now have exhibitions of dissected human bodies.

93. The Cockpit in Drury Lane, which housed Davenant's Opera in 1658, was not licensed, but connived at by the authorities.

94. The Elizabethan Playhouse (Second Ser.), p. 138.

95. The following data are drawn from No. 26.

96. The Black Books of Lincoln's Inn, ii, 414.

97. Ibid., p. 415. See also pp. 416, 417.

98. Strype's Stow (1720), ii, 119b.

99. Ibid. (1755), ii, 113b.

100. Annals of Tennis, p. 35.

101. Apology, (ed. Lowe), i, 314, 315.

102. Vol. iii, Parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields; Pt. i, Lincoln's Inn Fields, pp. 38, 48, 49, 52, 53.

103. Close Roll, 3988/17, Anno 1658.

104. Close Roll 4038/42, Anno 1659.

105. The data which follow are from No. 25.

106. Add. Charters 9296. See Appendix.

107. 9 April, 1668.

108. Lowe's Cibber, ii, 101, n. i.